By Martin Ihembe

After more than half a century of political independence, most countries in Africa are still grappling with the challenge of development with insignificant success. This is a sharp contrast when compared with their counterparts in Asia. The early years of political independence saw some kind of “pretext” to development by Africa leaders within the framework of African socialism (in contradistinction to classical socialism), and later Western-Centric ideologies, both of which were everything but successful. There has been a plethora of scholarship engaging the root cause of Africa’s development woes. Arguably, one of the most persuasive arguments advanced is the one by Claude Ake in his seminal work – democracy and development in Africa. Ake contends that “the assumption so readily made that there has been a failure of development is misleading. The problem is not so much that development has failed as that it was never really on the agenda in the first place. By all indications, political conditions in Africa are the greatest impediment to development.” Judging from the reality in contemporary Africa, this assertion can hardly be controverted.

In what appears to be a subtle critique of the dominant paradigms in development discourse as it relates to Africa in the social sciences, and in an attempt to proffer an idea that could help resolve Africa’s development gap, Dr Hyacinth Iwu has advanced what he termed the football theory of scientific development (FTSD for short) (still at its embryonic phase I suppose). As the name implies, it is a theory he conceived having carefully observed the game of football over the years. Consequently, he extrapolated the football analogy by advancing a theory of development he thinks is apt in addressing the protracted problem of underdevelopment in Africa.

In his analogy, Dr Iwu views tertiary institutions (universities, colleges of Education, polytechnics) as national teams that should serve as centres for harnessing and developing raw talents/skills. This is especially so given their role as conveyors of ideas. He assigned the role of Technical Advisors of the teams, if like Coaches, to professors. Lastly, he labelled lower cadre lecturers undergoing mentoring under the professors, students’, non-students’, and illiterate individuals as players. In his view, the latter category has latent talent that could be harnessed for market value. As Technical Advisers/Coaches, it is the job of the professors to scientifically harness these latent talents/skills by identifying and selecting them for economic development. To avoid the risk of running into conceptual confusion, and possibly conceptual stretching, Dr Iwu clarified what he meant by “science” in his theoretical postulation. According to him, science here means a “systematic process that is applied in the identification, selection, and development of any knowledge or skills”, which is to be done by the national team Coach. In this context, the professor. He equally stressed that in searching for young talented individuals as football Coaches do, the focus of the professors should not be on the socio-cultural or socio-economic background and other related characteristics but the skills inherent in the youngsters.

In his analogy, Dr Iwu views tertiary institutions (universities, colleges of Education, polytechnics) as national teams that should serve as centres for harnessing and developing raw talents/skills. This is especially so given their role as conveyors of ideas. He assigned the role of Technical Advisors of the teams, if like Coaches, to professors. Lastly, he labelled lower cadre lecturers undergoing mentoring under the professors, students’, non-students’, and illiterate individuals as players. In his view, the latter category has latent talent that could be harnessed for market value. As Technical Advisers/Coaches, it is the job of the professors to scientifically harness these latent talents/skills by identifying and selecting them for economic development. To avoid the risk of running into conceptual confusion, and possibly conceptual stretching, Dr Iwu clarified what he meant by “science” in his theoretical postulation. According to him, science here means a “systematic process that is applied in the identification, selection, and development of any knowledge or skills”, which is to be done by the national team Coach. In this context, the professor. He equally stressed that in searching for young talented individuals as football Coaches do, the focus of the professors should not be on the socio-cultural or socio-economic background and other related characteristics but the skills inherent in the youngsters.

Since the theory intends to elicit original ideas from talented people with a view of indigenising existing knowledge, included in the crop of players to be harnessed are illiterates outside the university and other institutions of learning. This aligns with the method of signing football players as we have seen in football teams in Europe, Asia, and America, where raw talent is the focus of the Coach, not race, facial look, certificate, or a potential player’s erudition in English, Spanish, or Chinese language. What matters most is the player’s talent which the Coach exploits maximally to brighten the chances of his team in the football market place – the League. Similarly, Dr Iwu advocates that professors as Coaches of national teams – universities and other tertiary institutions – should not enforce Mathematics and English on illiterate players – students – with talents harnessed out of tertiary institutions but simply observe them and ask questions in the language the students understand and can best express the skills they displayed in the innovations that attracted them to Coaches. This, in his opinion, will help in transferring the identified ideas to finished products for market value.

This approach to addressing Africa’s developmental gap using tertiary institutions is what Dr Iwu calls “indigenous scientific knowledge innovation”. In essence, Dr Iwu’s theoretical endeavour is aimed at evolving an autochthonous idea of development that is African in nature. Considering that the game of football has its origins in Europe, its autochthoniety is somewhat contestable like African socialism which was more like classical socialism.

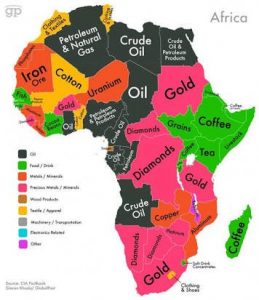

To achieve the assumption of the FTSD, Dr Iwu opined that Africa’s curriculum must be overhauled. In his view, the overhauling should be done in a manner that the curriculum is designed to elicit “creativity and innovativeness from primary to secondary school levels where technical skills are identified and harnessed among students for national development.” To a large extent, this argument holds true for a country like Nigeria. Doubtless, Nigeria is not bereft of talents and raw materials. These are in abundance. What it however lacks is the capacity to properly harness the talents and raw materials to its advantage in the global market place, hence Dr Iwu’s prescription on how to achieve that. So, at the basic level, perhaps reviving the technical schools and designing their curriculum to accommodate the much needed creativity and innovation at the primary and post-primary levels as Dr Iwu opined would be a good way to start.

In sum, Dr Iwu theory attempts to raise the consciousness of the academic community of its role in as the centre for harnessing talents which could be transformed for market value. While there are no absolutes in developmental pursuits as the FTSD appears to suggest, its core assumption is worth experimenting as Africa did with previous Eurocentric ideologies – Import Substitution Industrialisation, Infant Industrial Model, and Structural Adjustment Programme – advanced to it that failed.

Martin Ihembe is a postgraduate student in the Department of Political Sciences, @ the University of Pretoria, South Africa. Reachable via martinihembe@gmail.com. Whatsapp +2347036396194.