Depending on his flight path, Ambassador Jens-Petter Kjemprud must be back in Norway by the time this interview is posted Sunday evening, August 30th, 2020. He has been in Nigeria for the past four years as his country’s ambassador.

An earlier interview with Intervention failed but not this time, a day to his departure back home. Given where he is heading to on his return to Norway – the Norwegian Centre for Conflict Resolution – which has done a lot of work in Latin America, the Middle East and Africa too, Intervention was okay with the 45 minutes or so left before his next in the series of send-off activities on Saturday, August 29th, 2020.

Although he is not casual or bohemian, he is, nevertheless not your typical ambassador in terms of any airs around him. Perhaps too ideologically self-aware to be the archetype diplomat. He came off quite sincere or frank in the chat. Read on!

Leaving now after four years in Nigeria, the logical thing would be to open this by asking you about your overall picture of this country. But I want to reverse that and begin with Norway and, in fact, the Scandinavian countries. Some people say that the region is sending a message to the world by the relatively tension-free nature of the countries and the consistency of their high score in the Human Development Index reports. But what name might we call the message? Creative management of capitalism or a geo-cultural message or a ruling class project in one corner of the world?

I would like to call it the Nordic development model based on two things. One is the idea of Socialism at the turn of the century and the second is certain principles of Christianity in the Nordic countries. There are certain verses in the Holy Book that supports what we are talking about. But it is the Socialist catch which stretches from a strong heritage of trade unions, left wing political parties. I mean serious and well founded political parties with control mechanism to secure national interest and the working class interest. As you indicated, capitalism has its own ways of surviving. Because of this strong Socialist sentiment, capitalism has had to adjust in the Nordic area. That is the basis of what we have but which is now under serious pressure.

You paint the picture of where consensus has been achieved among contending interests

Amb Jens-Petter Kjemprud

Former Norwegian Prime Minister, Gro Harlem Bruntland @ the 51st Session of the UN in 1995

Yes. We had a Prime Minister in the 1980s. She once said that in Norway, we are all social democrats. She meant that even if you are of the right wing, conservative or whatever, there is a commitment to what we are talking about here. But her statement only reflected the reality at the time. Now, there is pressure.

Before I come to the question of where the pressure could be coming from in specific terms, perhaps you may like to give us a firsthand account of how the consensus was constructed and particularly by which agency.

The point is that, over time, there has been a tradition. There is, for example, a national trade union movement of one million members. That is the main trade union movement. People are generally organised along protecting their group interests. You get this either at the level of trade union or you have it in political parties or civil society organisations. Everyone is organised to protect certain interests.

What would be the problems of its replicability elsewhere?

I would say it is bound to be difficult to transport this elsewhere. It could be difficult, for example, to sustain membership elsewhere. I was a member of a far left party and I had to pay 10% of my earnings. To get people organised, they have to see the incentive. You won’t be a member of the NLC, (the national trade union in Nigeria) if you can’t see the benefit, if you are not sure you will be protected against being sacked

How might the society be organised to overcome the difficulties especially in areas where classical capitalism has been weak?

I served in Ethiopia before coming to Nigeria and I know the Prime Minister of Ethiopia then, Meles Zenawi and his colleagues had to ask for another look at this. They looked at different models – the Nordic model, the Chinese, the US, Singapore, South Korea and so on. At the end of the day, they concluded that African countries with huge populations would be difficult to organise in the image of existing models. They went for the developmental state model. That is what I have been missing here: to see a party on a question of where this country would want to be. When you look at the parties, you do not see clear ideological differences or where the party leadership can be kept responsible to the members. You have to have parties that are democratic.

The case for the developmental state model was very powerful here in Nigeria but strangely in the federal bureaucracy more than the political parties, especially after the First Republic. And that makes me want to ask you if you have any privileged idea of how the Structural Adjustment Programme in the case of Nigeria so successfully killed all such orientations.

You are talking of pre-IBB?

Yes

All over the continent, the SAP has had that effect. Beyond that, it is difficult for me to answer. I think it comes back to my previous point that you need political organisations to fight it out. Again, in Ethiopia, the government rejected the IMF-World Bank option and said that conditionalities or development models must be our own politically decided model. That was the language. There was stalemate in negotiation with the IMF because of that. So, they lost many years but, in the end, they got the IMF to change. So, you need people with strong political consciousness.

Still on Nigeria, where do you locate this story of start and stop every now and then?

I have met so many Nigerians all over the world, all very brilliant, especially in international organisations. For me, the answer to your question is back to my point about lack of willingness to organise. I believe politics is 20 % of thinking and 80% organising. You can have programs but if you do not have capacity to get the people behind you, it won’t work. During the 2019 elections, I had discussions with many political parties but they were not about organisations with grassroots backing around clear issues. I don’t believe in Facebook and Twitter revolutions. You have to have actual people organised. That is why I told the NLC that they are an example of an organisation that could create that kind of change.

Norway in the global space: small in population but a global statement as a critique of resource curse

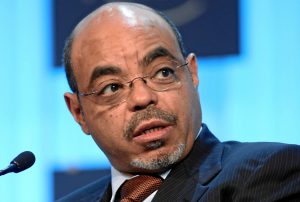

Late Ethiopian PM, Zenawi

So, with what fears are you leaving Nigeria?

I am concerned about how the security situation is deteriorating. In 2016, it was concentrated on the Northeast. Now, it is very much in the Northwest and the Northcentral. The concept of the national army is basically a force which protects the country from external attack. Now, the national army is engaged in 22 states in Nigeria. So, the army is fully engaged in internal security which is to show that insecurity is multiplying. That is my basic concern, especially that there isn’t that kind of resources to focus on root causes of most conflicts. Yet, there isn’t much of mediation and dialogue.

You didn’t see much of the transformative approach

Yes. The main answer is we have to resolve it militarily, not trying to resolve them at the level of the root causes

Could that have anything to do with the current crisis of consensus among the various fractions of the elite?

There is obvious lack of consensus. The very strong power of the constituent states means there is less unity of action. In the 1990s, you had the military government. That is not the situation now.

Do you have anything unique about approaching conflicts in Nigeria?

The conflicts we are seeing are diverse. They differ from each state to state and from conflict to conflict Just in Kaduna State alone, you have got three different types to address. The Northeast is different from the Niger Delta. But you still have something which is generic – approaching the other side. There has to be willingness to take advantage or lessons from other countries in reaching out to the other side. In the end, it is about how to find the common ground.

When you look at their framing of the conflicts, the reaction time and the likes, what is your sense of the Nigerian State in conflict management?

You don’t see a pattern coming from the central government. That’s one of the challenges with federal state. Imposing something from the centre is not easy. But it is more about how the central state sees it. If the centre sees it as all about military, then it could be a problem. Ethiopia was a strong central government but it is losing up now.

The assumption here is that the Nigerian State is watching the development in Ethiopia. As you may recall, Prof Mahmood Mamdani published an article in New York Times on the risks in ethnic federalism in Ethiopia. Six months later, there was a coup attempt. But you may also recall another paper here in Nigeria that asks whether the persistence of conflict on the continent is a case of conflict management failure or an endemic catastrophe. If you are reading that paper, which side of his two frames would you find yourself?

I would still say that you have to return to actual conflicts. But I don’t draw the line to ethnic federation. As I said, Ethiopia is losing up. That may be specific to its situation but I don’t see ethnic federation as the way to go. For me, ethnicity is identity politics and it is the wrong way to go. The state should take care of everyone. Our individual interest is too limited for politics to be based on identity. Identity is just one small part of a broader spectrum. There are so many examples of where identity politics puts the society in danger. With over 250 ethnic groups in Nigeria, it is dangerous.

The time is gone but we cannot end this interview without asking the question if Norway relates to Africa differently, perhaps with the Nordic lens and what that might have meant on the ground?

That is too much to ask of a country of just 5 million. We are just one country but based on one political ideology, not on ethnicity but on interest politics. Our contribution or should I say I would wish that people could organise because there is no difference between workers in Kano and workers in Lagos. The same thing for employers of labour who have the same interest. That way, nobody would have reason to align to religion and ethnicity.

Pleasantries!