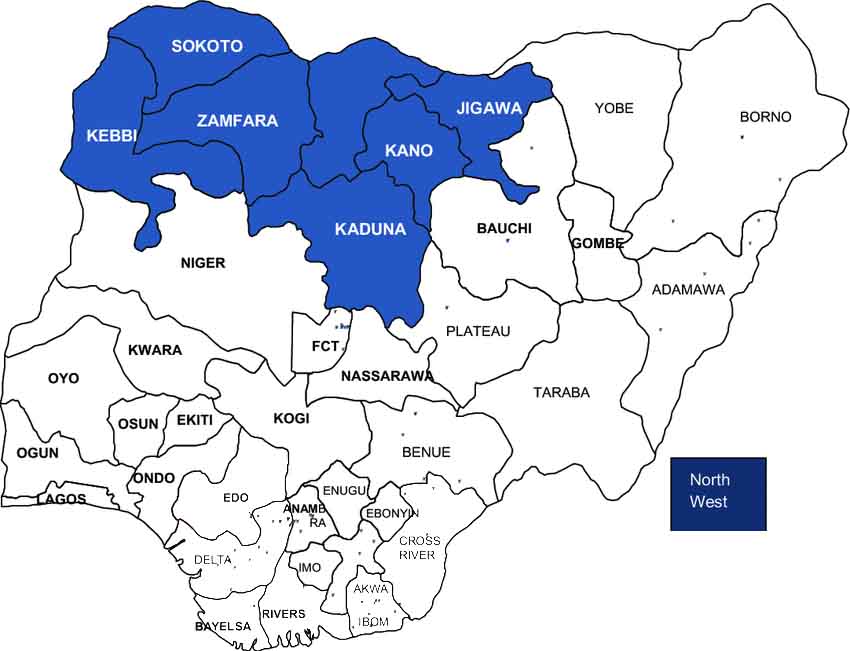

An attempt at unpacking the dynamics of corruption and conflicts is producing a narrative that favours the concept of ungoverned spaces as the key driver. In other words, discussants at a webinar on the theme today supplied data that suggests that, in the last instance, banditry and kidnapping in the region are products of the absence of the state. That is, absence of the state in terms of monopoly of the legitimate use of violence, justice and order. The exploitation resulting from that has forced people into banditry, one way or the other, said the speakers who added that this is compounded by dearth of leadership and mobilisation of the people. This is what they argue to have produced collapse of coherence between the community and the security agencies, rendering security intervention ineffectual.

Chief of Army Staff, Gen Buratai during a recent visit to the Emir of Daura in Katsina State

The presenter on “Corruption and the Challenges of Combating Kidnapping and Banditry in the Northwest of Nigeria” at the Centre for Information Technology and Development, (CITAD) organised webinar gathered data that led him to conclude that the traditional institution, judicial officers and security agencies are the key drivers of the violence. This happens when ordinary people who seek justice only get extorted and denied justice in the hands of traditional rulers, local judicial authorities and sundry middlemen. The researcher, therefore, draw a link between the crime of banditry and kidnapping on the one hand and frustration on the other hand.

To the list is added security agencies – the police and the local vigilante in particular. The context of professionalism of the officers and men of these agencies, noted the researcher, is such that is provocative of corruption. The DPO has just N3000 imprest. It was not clear whether the researcher meant this is a weekly or monthly amount but whichever one it is, it speaks to how that institution has basically no resources to guarantee law and order. Besides, it was mentioned that most policemen are not only poorly trained and basically unarmed but have to use their own money to carry out official duties.

Finally, the politicians whose involvement is at several levels, the most significant being complicity in the arming of thugs and hooligans who, when abandoned after every election, turn to those arms as a means of survival.

His counterpart on “Corruption and Complicity: Community Resilience and the Zamfara Conflict” tried tracking the banditry in the state to a void created by abolition of cattle tax by the governors of the People’s Redemption Party, (PRP) in Kano and Kaduna states in the Second Republic. But the void and the tussle it provoked has since transformed into herder-farmer conflict and transformed further than that. The presenter argues that violence in Zamfara is not a case of conventional radicalization or response to any specific claim of marginalisation. In other words, it is a classical case of post Cold War violence – driven by no ideology, very irregular and destructive army.

In shifting the gaze to the mining dimension of the violence, the presenter sees a link between the agenda of diversifying the economy and the subsequent restructuring of the sector only to transform the artisanal miner into the illegal miner. The illegal miner, in this context, is only so discursively because, in truth, such miner(s) are actually certified and licensed but probably only materially not in a position to contest being positioned as an illegal actor. Interestingly, the ‘illegal’ mining sites are also the sites in which bandits are concentrated.

His third main point is the collapse of community resilience arising from destruction of the bond between leadership and the followers. The leadership which is seen as benefitting from the crisis has automatically lost communal trust as to be able to do anything productive.

Inspector-General of Police, Mohammed Adamu

The third presenter who spoke on “Unpacking Corruption-Human Rights Nexus: Implications for Governance, Security and Development in Nigeria” itemised various manifestations of the nexus between corruption and human rights, human rights defined broadly to encompass socio-economic rights to food and the likes. On his list are hijack of state institutions for private interest, the length of time it takes to convict corruption suspects, taking up to 12 years in most cases; the diversion of funds of peculiar dimension such as the N1trn Constituency Expenditure by the legislature. His list is much longer.

What are the efforts by the government to deal with this situation and how adequate are those? His argument is that there have been efforts but it is debatable if they are adequate. One is the phalanx of anti-corruption agencies – EFCC, ICPC, CCT and so on. Newer initiatives such as the FOI Act and the whistleblower instrument were listed as well as civil society initiatives such as the ‘Follow the Money’ campaigning, among others. the National Human Rights Commission, (NHRC) widening its conceptual practice of human rights is one out of four suggestions the presenter put on the table.

A number of questions greeted the presentations. Only one will be noted here. A participant wanted to know about the external dimension of banditry. The reply was that it makes logical sense to think of that, especially from Niger, Benin Republic and even Mali and in the context of the involvement of foreign companies in illegal mining. But it was stressed that unless there has been more detailed profiling of bandits, it will be difficult to reach that conclusion stick to such a view.

All three presenters came up with impressive data in each of the presentations although they would appear to methodology critics to still be following the data rather than otherwise. A strong hunch that disciplines the data into an irresistible argument about the conflict in question appears to still be in hiding, perhaps out of shy. One of the presenters appear to recognise this by stressing lack of political leadership as the driving force or the root to which the various dimensions of the violence are traceable. Perhaps this did not come up that strongly because the field is still guiding the research.

Methodology buffs are also saying they didn’t hear anything about the identity nuances of respondents. While noting how impressive is the data of the first presenter who relied on key informant interview, they worry that the researcher could disconnect the data from the specific discursive insight which produced them if the respondents are not identified by what they call themselves, That is, it is tempting to see most dwellers in the Northwest as Muslims, peasants or of urban poor but such huge labels hide too much to reveal what is sometimes the most important dynamics of what is being investigated. Like all such researches, the research report would then be addressing data but not human beings. It helps when respondents in a social research are identified beyond broad groupings. Failing to do so accounts for resurgence of violence because it cannot be all bandits who are into that to protest extortion, (corruption) by local structures of domination, for example. The search for resolution must account for their own incentive to violence as well

The discussion has, however, kicked off with great promise!