University of Ibadan political scientist, Prof Adigun Agbaje was a year older recently. It is either that he doesn’t particularly fancy the culture of elaborate festivities for a birthday or COVID 19 ensured that he could not even contemplate that. And so, the birthday appears to have passed quietly, except for those in Ibadan who might have shared drinks quietly while watching out for fierce guys enforcing COVID lockdown in Gov Makinde’s territory. But, a birthday is a birthday and some form of celebration must be going on up there in the cranium. To that extent, this is an interruption. But this is a justifiable interruption in that Adigun Agbaje is one of Nigeria’s political scientists whose birthday should have been an occasion for collective reflection on the discipline in Nigeria in general and the role of theory in the project of remaking Nigeria in particular.

Decidedly conservative late Prof Kenneth Waltz but yet the most authoritative voice on what a theory is, till today

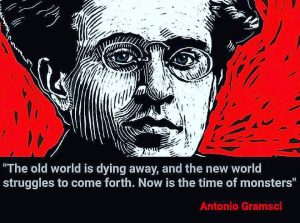

Robert Cox of “every theory is for someone and for some purpose” fame, the aphorism underpinning Gramscian political economy

Theory is all that we have. Thank to God, it is also all that we need. Positivism misled Marx to make a binary pair of interpreting the world and changing it. But, very early and within Marxism, this was corrected with the formulation that there cannot be a revolution that is not hooked to a theoretical lens. Hegemons are not hegemons because they have awesome military machines. They are precisely because they skillfully learnt from Lenin that they can sing a particular reality into being. And the weapon for that is theory. Shorn of the mystification, a theory is nothing but a statement in power relationship. No major theorist has argued against this of late, from Ken Waltz to Robert Cox to the entire post-positivist gang. So far, no one else has anything better to say about what theory is than the consensus of these names who are coming from distant traditions as neorealism, Gramscian political economy and reflexivity.

Lenin’s statement laid the foundation but did not resolve the difference, a gap that Gramsci stepped in to fill and which the students of the ‘linguistic turn’, especially of the Deconstruction School have taken to its current limits in the works of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe in particular.

This background makes the Adigun Agbajes of this world people to sit down with and go over the question of what theorising brings to the table and why the three of them from political science who went to study the mass media as the space for manufacturing hegemony did so at the time they did. The three, as far as this reporter can recollect, are Agbaje, Jibrin Ibrahim and Bala Jibril. Bala Jibril, a product of the University of Lagos School of ‘Mass Communication’ and later of Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria’s Marxist political economy has gone to meet his maker but Agbaje and Ibrahim are still here. There might be others in Mass Communications, International Relations and Geopolitics who have studied hegemony too. And to think that these three did so long before Social Constructivism and the ‘linguistic turn’ took the theoretical and methodological centre stage in academic politics makes it even more splendid. It shows how great Nigeria was moving before the locusts descended on it and complicated existence for everybody.

Okonkwo thrashing Amalinze

In the case of Agbaje, there is the bit about obtaining a First Class in the social sciences, an achievement that did not benefit from his Yoruba-ness or his religion or a capacity for sycophancy at the time. Rather, it is the sort of thing Achebe credits Okonkwo in Things Fall Apart as ‘solid personal achievement’. That’s Okonkwo rising through unassisted barrier breaking exploits, particularly the very open and transparent wrestling between him and Amalinze the Cat whose back never touched the ground. Okonkwo made that back to touch the ground, not by running from pillar to post but in a wrestling observed by the republic: elders, women, young ones and the different age grades.

In the case of Agbaje, there is the bit about obtaining a First Class in the social sciences, an achievement that did not benefit from his Yoruba-ness or his religion or a capacity for sycophancy at the time. Rather, it is the sort of thing Achebe credits Okonkwo in Things Fall Apart as ‘solid personal achievement’. That’s Okonkwo rising through unassisted barrier breaking exploits, particularly the very open and transparent wrestling between him and Amalinze the Cat whose back never touched the ground. Okonkwo made that back to touch the ground, not by running from pillar to post but in a wrestling observed by the republic: elders, women, young ones and the different age grades.

This is a point we probably take lightly in terms of the social statement embodied in a First Class at that time for a corrupt country such as Nigeria. It is in the attitude of present day students that a First Class is not as important as who they or their parents know in government. How does anyone build a country that way when those who will be in charge tomorrow are formed this way?

In other words, First Class at the time Agbaje accomplished it unlike what it is today is as great as what Agbaje privileged in scholarship – the idea of power through hegemony. The foresight in that is something in its own class because it is not like today when hegemony circumscribes not just knowledge in whichever realm you take but also political practice. Of course, the study of hegemony has moved from what Gramsci said it helped to do but whatever the changes that have taken place, Hegemony and Structuralism (to the extent that poststructuralism originated here) have set in motion idea of Emancipation, freedom, democracy and human rights in a way that is truly revolutionary.

How could anyone have imagined the degree to which reflexivity has reshaped a very, very conservative subject such as International Relations? Yet, that is exactly what is happening and to the extent that the discipline is decolonising itself so as to step back from the picture of its complicity in 9/11 that Prof Steve Smith, for instance, presented in February 2003. So powerful that the subsequent decolonial project must be to its credit, at least as a defining trigger. To the extent that Smith’s scholarship is a product of the fierce battle between Rationalism and Reflexivity from 1988 to the immediate post Cold War, to that extent do Constructivism, poststructuralism, feminism and postcolonial theories have been erecting a more equal and just world by rupturing the Enlightenment categories of reason, truth, progress and universalism, the operationalisation of which explains the horrors of contemporary history.

Predicting the first quarter of the 21st century from his prison cell in the 20th century

Reading much of what people write and/or say in Nigeria, one gets the impression that the details of the struggle that brought about this rupture in knowledge, the heroes of the struggle and the political and organisational implications seems not to be part of the consciousness of many who ought to know as it relates to radical politics.

And here, we turn to Agbaje again. One of the things he said in 2011 while declaring open a CODESRIA Methodology Workshop at the University of Ibadan is that Africa will continue to be ruled from outside as long as it cannot frame the world. He was sure that Africa could do with what Okello Oculi would call ‘horizon sketching’, something similar to how Latin America, for instance, was able to problematise Marxism to produce a theory reflecting its historical and geo-spatial experience. On this, Agbaje was absolutely correct. Nobody needs look far beyond the Zapatista Movement successfully confronting the might of NAFTA by completely reversing the order in the rule book in moving from a ‘war of movement’ to a ‘war of position’. In other words, it started with armed resistance only to abandon it in favour of creating narratives and constructing a ‘historic block’ around its claims. Or, how the equivalent of a historic bloc constructed a radical narrative of indigeneity in Bolivia, bringing a president to power through election. Indigeneity which is supposed to be a dirty or counter-revolutionary vocabulary by orthodoxy became the rallying point of middle class intellectuals and professionals, indigenous fronts, landless peasants and urban poor because a word has no static meaning which should make it ridiculous for radical activism outside of space and time.

There are absolutely nothing in Nigeria, for instance, comparable to these examples in creativity from Latin America, meaning that imprisonment in orthodoxy is challenging Lenin’s thesis of no revolution without a revolutionary theory here. Surely, questions of what it means to talk about ‘historic block’ instead of the working class or to talk about antagonism instead of contradiction or emphasizing articulation instead of class alliance do not appear to form part of the radical democratic agenda around this place. But how then might complexity and fragmentation be addressed? How might the falcon be made to hear the falconer in a highly pluralistic formation such as Nigeria? Yet, it is a decade or so that Agbaje pointed this out as much as possible.

Prof Eghosa Osaghae

Prof Jibrin Ibrahim

It seems this is an opportunity to be explored towards a gathering of that generation to look back. Political Science in Nigeria is not only empty of the teaching of Hegemony, it is even drier of the ‘linguistic turn’ in social analysis, not to talk of the ‘textual turn’ and the similar turns. Not that it has much to say on the classics either.

Prof Agbaje, Jibrin Ibrahim, Sam Egwu, Eghosa Osaghae, Okey Ibeanu, Attahiru Jega, Adele Junaidu, Bolaji Akinyemi, (who one understands was still able to attend the last NPSA conference in Calabar), Ogban Ogban Iyang and all the other established as well as rising leaders in the discipline that one cannot recall immediately cannot be physically and intellectually around and the discipline would be drying up. This is because, as it dries up in the universities, so does the possibility of radical democratic politics takes the last seat at the farthest end of the hall. Anyone who challenges this must tell us why what NANS could do in the 1980s has now become impossible in Nigeria of the post 1999. The risk is, therefore, too frightening to leave things as they are when something can still be done. Certain people who have climbed higher on the ladder have a higher share of the burden of doing something.

An apology to Prof if this has disrupted the birthday mood. It can resume. Wishing Prof many more years of an exciting evening of life!