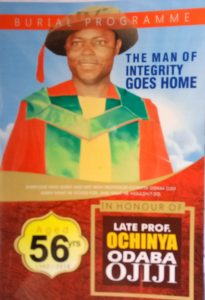

Written by Prof Ochinya Ojiji of Nasarawa State University’s Department of Psychology, A Dictionary of Social Science Research attempts breaking down the common terms that a new undergraduate confronts in the understanding of methodology. Being a Psychologist which, along with Anthropology, was more innovative in applying the so-called scientific method, it was not surprising he was that concerned. As he himself stated in the Preface to the 2012 publication, he had observed the difficulties that students face relating to key concepts in social scientific research “in over two decades of teaching social science research methodology courses to both undergraduate and postgraduate students across the length and breadth of the Nigerian university system”. He is referring to the University of Jos, the University of Uyo, the Institute of Peace and Conflict Resolution, Abuja and Nasarawa State University, Keffi. Of course, he was an award-winning doctoral product of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka when the universities were much tougher than now.

The simplicity of his approach recommends the book for starters. What he did was to take as much of the key concepts he could, place each of them under the appropriate alphabet and try to define or explain what it refers to. So, anyone who encounters the book will get to encounter all those slippery concepts in research methodology such as abstraction; alternative hypothesis; a posteriori test; bimodal distribution; canonical correlation; cohort effect; debriefing; deductive statistics; ecological validity and empiricism.

The simplicity of his approach recommends the book for starters. What he did was to take as much of the key concepts he could, place each of them under the appropriate alphabet and try to define or explain what it refers to. So, anyone who encounters the book will get to encounter all those slippery concepts in research methodology such as abstraction; alternative hypothesis; a posteriori test; bimodal distribution; canonical correlation; cohort effect; debriefing; deductive statistics; ecological validity and empiricism.

Others would include feminist research; frequency polygon; grounded theory; heteroscedasticity; illusory correlation; Likert Scale; marketing research; methodological errors; omnibus test; one-tailed probability; parametric statistics; paradigm shift; participatory research; regression fallacy; semantic differential scale; scientific revolution; social mapping; transformation of data and so on and so forth, spread over 93 pages.

These concepts might look simple or straightforward on the face value and what with the use of local examples but not so when located in the problematic realm of how do we know that we know what we think we know. In other words, the question of how might we be sure that what we think we know is what actually exists? This is still the toughest question in human history. It is the methodological question which students dread in higher schools and which citizens all over the world confront everyday without even knowing it. There has never been a stable answer to the question. The answer keeps changing.

Initially, truth came from revelation. Then there was the Enlightenment revolt against kings and nobles who were misusing the name of God by saying they were representatives of God on earth. The struggle against them led to the rise of science as the only way to establish truth. That is what Enlightenment movement in the West contributed to humanity. It marks the era of Positivism.

Science has been reigning unchallenged for hundreds of years. For science, proof of truth lies in what can be seen or touched, not anything like sixth sense, (instincts) or metaphysics, no matter how intelligible because, the revolutionaries who led the Enlightenment revolution didn’t want to give room for any group or class or interests to claim that they derive power from any other force that could not be observed. For them, truth is something that is out there and can be discovered if one does a careful research. That means they separate the researcher from what he or she wants to discover. The correct language for that in positivist research is objectivity, the idea that the religious, ethnic, gender, class and locational values of the researcher should not interfere with the study or it would no longer be objective or be considered scientific.

Anyone whose undergraduate son or daughter has not been taught this book has the right to ask the university why

Including its criticisms such as this

Positivism has come under attack in the aftermath of the post Cold War and even before it. Those known as Post-positivists do not accept much of the grounds stated above. They describe as nonsense the idea that objectivity can be possible or a necessary condition for secure knowledge. They dismiss the possibility of secure knowledge altogether, saying that any knowledge that is not provisional and contextual is totalitarian. What is right in the United States, for example, cannot and should not be necessarily right in Nigeria because human beings are not like water, for example, which boils at 100 degrees centigrade universally.

Truth, they say does not lie out there to be determined through objective research but in the mind of the researcher. Their popular witticism for that is that “we do not see the world the way it is but the way we are”. That means they necessarily do not accept universalism but, instead, emphasise difference and insist on inclusiveness. It explains the rise of the use of perception as the way to truth today and, by implication, the return of sixth sense, ‘magic’, culture and all manner of metaphysics today.

This background do not appear in this form in the book but are embedded in each concept he defines, especially those such as empiricism, philosophy of science, critical theory, constructivism and so on. Suffice to add that methodology is an ideological or political issue, not an academic issue at all. As long as the traditional institution and religion were in power, revelation was the standard methodology. To overthrow them in the continental revolutions in Europe and North America, (English, French, American revolutions), the radicals who led those revolutions had to come up with their own methodological framework. Some people would say that to completely cripple the powerful order they were fighting, they defined the scientific method in a way that they forgot God, emotional attributes such as love or passion and the role of the human mind, the power of ideas and norms, of culture, passing these subject matters to a discipline such as Literature which continued to grow from strength to strength in the age of science to everybody’s surprise. Today, the values of science, reason and progress that Positivists posed in the Enlightenment are exactly what Post-positivists are using against them: that science is unreasoning, that reason is not prevailing or there would not be so much wars and atrocities and that Enlightenment has failed as far as progress is concerned. Above all, Post-positivists say that this is the post-modern era, so fragmented as for grand narratives/universal truths not to be too homogenizing, too exclusionary and too dangerous for difference and inclusivity. It is from their decentering of truth that we have what most people now call post-truth, the management of which has become a big research project in many centres of knowledge production across the world.

Without bringing back memories, it is unfortunate to recall that Prof Ojiji is late by a year and a month now. But this book and his several academic essays ensures that we continue our conversation with him. He was, indeed, a social scientist. Before his sudden death, he was framing a research question. He wanted to find out which is more powerful than the other in everyday life: membership of one soccer club or membership of one ethnic group. That is, would two persons involved in an imaginary car crash on the road reconcile more quickly if they discover they are all Arsenal fans than if they discover they are all of one ethnic identity? Of course, he would not frame it as crudely as this. He hadn’t completed the framing. He was still working on it. Maybe, one of the students whom he supervised might take it up!