By Dr. Patrick Wilmot

On the whole, this text, the person who delivered it, the subject and the issues thrown up will all infuriate many in Nigeria today because it is too soft on some and too caustic and unsparing of some others. But re-publishing the text is a duty to Nigeria for the analytical breadth of fresh air it offers at a time at a time when no game changers are in sight. Nigeria is certainly in that condition of discourse incoherence Hobbes called ‘the state of nature’ where there is war of all against all simply because the society could not reach a common position. Hobbes’ state of nature was not a physical war.

The address might read differently if delivered today but the caustic attack on some notables is not the issue here. Instead, there are three points. One, many of the issues raised in the speech 12 years ago are still with us. Two, they have been raised by someone well located to raise them. Three, it gives us a critical celebration of a recurring name in the Nigerian polity – General Yakubu Danjuma and again by someone who worships only at his own wavelength of independent mindedness: Dr Patrick Wilmot. One more sentence on Danjuma in this regard.

General T Y Danjuma has not spoken of late but he is in the news. His “they collude” alarm of 2018 is echoing to the eternal embarrassment of a nation already shocked to a state of unshockability, with due apologies to the late Dele Giwa, the original coiner of the phrase.

Intervention invites readers to savour this abridged version of the address delivered by Dr. Patrick Wilmot at General Danjuma’s 70th Birthday held at the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs, Lagos on December 7th, 2007. The original title of the address is “General Yakubu Danjuma: Patriot, Soldier, Statesman”:

By Dr. Patrick Wilmot

Dr Patrick Wilmot, (1st from left) with other citizens of the ‘Socialist Republic of Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria’ in those days. Next to him is the late Dr. Yusuf Bala Usman in this twitter sourced pix

First let me congratulate General Danjuma on achieving the biblically sanctioned quota of three score and ten years. I’m sure you all would wish to join me in saying Happy Birthday to the General, his family and nation, and to wish him another score of years if God so wills it.

We all understand that there is no point in celebrating the length of one’s years, if this time was dedicated to doing evil to one’s country and one’s fellow men and women. Personally I would not be here to celebrate this man’s birthday if he had spent most of his seventy years bringing disgrace to his uniform and reputation as a patriot.

The General is a brave man: how many generals or ex-generals in the Nigerian army would consent for someone like Patrick Wilmot to dissect seventy years of his performance on the national stage? I know that even some of my fellow intellectuals are unhappy that I’m here today, that I’m even still on this earth! God bless them.

General Danjuma co-operated with Lindsay Barrett in writing the book Danjuma: The Making of a General in 1979. Lindsay is another ‘troublesome’ Jamaican who has been in this country for more than forty years. If the General was confident enough to allow such a book to be written, it means he had nothing to hide because Lindsay is not known as a liar or praise singer who would sacrifice the truth to present a false picture of enduring brilliance. Lindsay knows many other generals but none has allowed him to write a book. I do wish, however, that he would do a book on our late friend, the fellow poet, General Mamman Vatsa, who helped him write this book on a professional soldier, who inspired and nurtured him.

The first time I met the General was at the naming ceremony for his child at the military school in Zaria in the early 1970s. As a lecturer at ABU, Zaria, I was quietly sipping my Star when the General sent his batman over to take my beer away and give me a glass of champagne. He explained that this was a military establishment, not the Socialist Republic of ABU! I was impressed – not many men would have had the audacity to pull such a stunt. Unfortunately, I have not seen the child since, but I hope that she has followed in the footsteps of her father, and is now contributing to the welfare of his nation.

The African leader that General Danjuma most reminds me of is the late Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, the ascetic President of Tanzania, who sacrificed his life and pleasures for the development of his continent. Like President Nyerere, the General is an intelligent, modest, soft spoken man of integrity, who did not throw his weight around as a leader, thought he knew it all, or fattened himself at public expense.

One of the ‘crimes’ I was supposed to have committed in this country was to refer to ‘brain-dead, pot-bellied generals.’ I never used those actual words, but in defence against this false accusation, I insist that war is a complex business, which the brain-dead cannot organize, and no soldier worth the name can afford the indignity of a potbelly, no matter if he’s 66 or seventy.

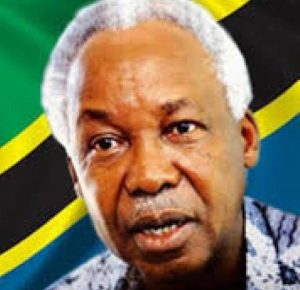

The late Julius Nyerere, the University of Edinburgh educated first leader of the Republic of Tanzania

I mentioned late Mwalimu Nyerere not only because he was a great leader. Yakubu Danjuma knew the Mwalimu, because he was sent to Tanzania when Nyerere was having some local difficulties with his military in 1964. The General was equerry to the President when he came on a visit to Nigeria that same year. Like the General, the Mwalimu was a plain spoken man who did not suffer fools lightly, and would have said so if he didn’t think Danjuma was up to scratch. He would not have been made an Equerry if he did not get along with the Tanzanian President. So outspoken was President Nyerere that he once asked a military President of Nigeria how he could afford such a big farm on his salary. Despite his time in office, Nyerere left a small, ramshackle farm when he died, and resisted the pleas of supporters to stay in office for life.

The General would have been impressed with the simplicity and directness of this African leader, who did not steal public funds, but used the scarce resources of his country to foster the education, health and welfare of his people. Yakubu himself had been brought up by good, loving parents who taught him not to steal, lie or make a spectacle of himself.

The discipline and integrity he learned in this loving family atmosphere allowed him to appreciate these qualities in someone like Nyerere who, despite the poverty of his country, was making such tremendous contributions to the liberation of Southern Africa. Nigeria’s contribution to the fight against apartheid, and its elevation to a Frontline state, was influenced by this encounter between the General and the Mwalimu, which helped explain the dynamism of Nigeria’s policy on the region between 1975 and 1979.

Generals Murtala Muhammed and Yakubu Danjuma and M.D. Yusufu were three of the men in the Supreme Military Council who crafted the policy on Angola which dispensed with Nigeria’s slavishly pro-Western stance, and put the country forward as a definer and protector of the continent’s national interests. Before this bold move Nigeria had reflected the colonial political brainwashing which labelled as ‘communist’ any African policy which opposed Western interests, even if this was 100% in favour of African development.

Although the great speech which encapsulated this policy was delivered by Murtala Muhammed in Addis Ababa on 11th 1976, it reflected the philosophy of Yakubu Danjuma and other members of the governing body, which gained them almost universal support from the Nigerian populace while their rule lasted. They gained public acclaim when they staged a ‘coup’ against the late Foreign Secretary who had assured Henry Kissinger Nigeria’s support for the bogus Angolan ‘Government of National Unity’ was in the bag.

When Murtala was assassinated almost a month after the Addis speech, Danjuma’s name was on the list of those scheduled to die at the hands of those who refused to accept the need to change. But instead of going into hiding out of fear for his safety, leaving the fate of the nation and continent in the hands of political vultures, he stood firm and organized the counter coup which defeated the forces of reaction. The coup effectively unravelled when Bisalla heard that Danjuma was still alive. Bisalla fled, went into hiding, some of his collaborators took to their heels, and order was restored. This is what is expected of a soldier, to face the fire, not run from the battlefield, or bargain with the enemy in case he came out on top.

Although the Murtala regime, of which Danjuma was the military foundation, was not elected, it had the support of the overwhelming majority of the people. Danjuma’s crushing of the coup was possible because the people were totally opposed to the killing of Murtala. On Friday 13th February, even before we knew whether the coup was successful, students were in my house demanding that I address them at a rally in support of the regime.

When I advised caution, and suggested that they wait to learn details, they said they needed no time to learn anything, and that I of all people should jump to the chance to support the regime, since they were implementing policies I had been teaching them in the classroom over the years. I was proud of these students since they taught me things I should have known: that when something is right you must defend it at all costs. I was a foreigner, I could be killed or expelled if Dimka and Bisalla came out on top. But I went to the assembly hall, spoke alongside the late Bala Usman, and my speech was published in the New Nigerian, which was then the Nigerian paper of record.

An internet pix showing the trio who ran Nigeria in the mid 1970s – Murtala, Obasanjo and TY Danjuma

Not long after the killing of Murtala, I learnt that a member of the Supreme Military Council suggested that that ‘Jamaican lecturer’ from ABU be expelled from the country. Another member asked the reasons and was told ‘he’s always writing and speaking about affairs in Southern Africa, in South Africa, Angola, Mozambique and Namibia.’ To which the other member replied: ‘Is this not the policy of this country, which this Council has sworn to uphold? We should give the man a medal instead of deporting him.’

This was said by General Yakubu Danjuma, who had refused to take over the political reins from Murtala because he thought it more important to reorganize the army, to make it a modern military force, subject to discipline, honour, integrity, and esprit de corp. There was no doubt that this General would have made a better Commander-in-Chief, and that Nigeria would have been spared many problems which later beset it through corruption, indiscipline and stupidity. But the General had set himself a task to make the army so disciplined that it would avoid the horrors of January and July 1966, the Civil War and the assassinations of February 1976. As the most respected soldier in the army he knew he was the one to do this, and pursued his goal ruthlessly.

If his successors had had the honesty, integrity, discipline and intelligence to modernize the politics and economics of the country, Nigeria would today have a modern army among the institutions of a 21st Century state. It would not today be the laughing stock of the international community, in which its people lack water, education, hospitals, security, electricity, housing and public transport.

One of the reasons Yakubu Danjuma was respected in the military, was that he told the truth, and was not afraid to speak out, regardless of the consequences. He would never rejoice in being named after a football player noted for his cheating, dishonesty, cocaine sniffing, vulgar tattoos, corruption, and obesity. The General was a ‘straight’ man, one you could trust, whose promises and words were worth something. He was not a dribbler, a man who lied to himself, whose words were not his bond, who climbed to the summit on a mountain of corpses, including that of his best friend.

When General Gowon broke his promise to relinquish power to democracy in 1976, Danjuma spoke out about the negative effects of a soldier breaking his word. He had also pleaded unsuccessfully, together with other patriotic officers, that General Gowon replace the most corrupt and megalomaniac of his governors, who were bringing military rule into even more disrepute. As a brilliant soldier he understood that military rule was a mistake, which needed to be corrected as soon as possible, so that the military itself would not be a victim of its own interference in politics it did not understand, and could not operate.

He recognized that Nzeogwu’s attempt to clean up the political system had failed and that the military itself was magnifying the flaws of the civilian politicians. The role of the military in the 1980s and 1990s, which destroyed every institution in the country, including the military itself, showed that this fear was grounded in reality. When the time came for military dictatorship to end in 1998, he thought that his friend, who had done the job before, and had suffered the inhumane tortures of prison, was the man to restore democracy. As Minister of Defence he saw that democracy was not happening and was not afraid to say so. He wanted to leave before 2003, when he saw democratic principles being violated, and left before the ‘elections’ which were unworthy of an ex-officer and ‘gentleman’.

Chief Obasanjo who earned General Danjuma’s respect for drawing up the plan that ended the Nigerian Civil War and for being an efficient Chief of Staff, Supreme Headquarters under Murtala

General Danjuma opposed the Third Term conspiracy for the same reason he opposed General Gowon’s attempt to continue in office in 1976, and some leaders attempt to prolong military rule in 1979. It was dishonourable, a breach of political trust, even if the government was doing well. But by 1975 the Gowon government had run out of ideas, and could not solve the simple problems of supplying petrol, or clearing the harbours of cement, which was bankrupting the country through fraudulent demurrage.

By 2006 it was clear that after seven years the government had not solved the problems of education, water, power, health, housing, social welfare, security, roads, railways and public transport. The military was incapable of suppressing the hemp smoking kidnappers of children in the Delta, denying the treasury trillions of Naira. Members of the ruling party were using the ‘militants’ to steal oil and terrify innocent citizens. Under these circumstances, the Third Term was not just dishonourable but criminal. The General’s wife Daisy, who was a Senator, did not support the Third Term either, and was vocal in saying so. So she became an ex-Senator for her honesty as Baba does not take ‘No’ for an answer.

Yakubu Danjuma is a man intelligent enough to know what is wrong and courageous enough to come out and say it. The cult of silence is one of the greatest failings of public figures in this country, especially intellectuals who have the privilege of acquiring and disseminating knowledge. General Danjuma had the intellectual ability as he showed from his performance in secondary school and the Nigerian College of Arts and Sciences, the precursor of Ahmadu Bello University. He became a soldier because he wanted to, not because he could do nothing else. He attended some of the most prestigious military institutions in this country, the United Kingdom and United States. His mother who was literate, must have been partly responsible for his love of learning, while his father taught him the need of integrity, courage, honour and discipline.

With this intellectual ability the General was not afraid to interact with intellectuals who could interrogate his actions or his values. He looked for challengers not praise singers, to help him see reality in a new light. That is the vocation of the intellectual, the ability which enables him or her to question the status quo, and allow progress to occur. The true intellectual has values, most important of which is to speak out when s/he sees evil occurring. In this sense the General is an intellectual soldier because he has always refused to adhere to the cult of silence.

In Germany when the Nazis were destroying their country and the rest of the world, there were courageous people who opposed Hitler at the cost of their lives or comfort. The Pastor Martin Niemoeller said ‘First they came for the Communists,/and I did not speak up/ because I wasn’t a Communist./ Then they came for the Jews,/ and I did not speak up/ because I was not a Jew./ Then they came for the Catholics/ and I did not speak up/ because I was a Protestant. Then they came for me,/ and by that time there was no one/ left to speak up for me.’

These are words of courage which earned Niemoeller torture in concentration camps. These are words that Yakubu Danjuma could understand and identity with. He has never locked up or killed a journalist or critic, and I know he was a friend of the late Fela, and visited his Shrine. One’s attitude to Fela is a good measure of one’s ability to judge people. Fela was a rebel but many of the values he espoused – his honesty and courage – were ones worthy of emulation. He was also a musical genius. That’s why M.D. Yusufu and the late Murtala Muhammed were also friends. Fela was from a family which stood up for the rights of the people. One remembers how his mother organized the deposition of the corrupt Alake of Abeokuta, and how his brother helped fight the dictatorship of Sani Abacha.

When the late Sekou Toure came on a state visit to this country, he sent for Fela, causing displeasure to his host who hated the musician. But Sekou Toure explained that he was the Patron of all the artists like Fela in his country, because they were in touch with their people, and could destroy him at the next election with a single song. Unfortunately his host had nothing but contempt for the people, and was disgusted when the musician turned up with a molue packed with his wives and copious supplies of Indian hemp. General Danjuma met Fela when he came to try out for the army band, and although he didn’t get the job because he quarrelled with everyone, this did not make him regard Fela as an enemy for life.

Gani Fawehimi, who has attacked and criticized every government in this country, could also identify with Niemoeller, who did not believe that government was sacred, and knew that it was the citizen’s right to criticize. Mallam Aminu Kano was an incarnation of Niemoeller: General Gowon had to send someone to remind Aminu that a cabinet meeting was about to begin, when the Mallam was out marching with workers demonstrating against Gowon’s government, in which he was a senior Minister.