By Adagbo Onoja*

General Chom Bagu is in the news again, this time, for one of his latest Facebook posts. For those who might not know him , that is the name of one of the intellectuals of activism in Nigeria. If you want to carry war to him, you have to be well prepared. His intellectual and political constitution is not a weak, wobbling type. He is not mealy mouthed either. In other words, he is not called a General in the annals of activism in Nigeria for nothing. He is a warrior, from whichever angle you encounter him, what with his Crocodile skin to upbraiding.

Cardinal Onaiyekan,

Gen Chom Bagu

Certainly, he is not the first Middle Belter to have said what he said. To call John Cardinal Onaiyekan a Middle Belter is to localize a global citizen but he is a Middle Belter in territorial terms. And it is instructive that he has said nearly exactly what General Bagu is saying. The difference might be that he did so with the candour or language corresponding to his grooming as a Catholic priest and his social standing. That is probably why his might not have cut as painfully as Chom’s. Otherwise, as widely reported in the media on July 2nd, 2017, the then Catholic archbishop of Abuja, urged Christians to “Christianise Nigeria” and stop complaining about the alleged plot to Islamise the country.

Celebrating the Sacrament of Confirmation at Our Lady of Perpertual Help Parish, Gwarinpa II that year, Onaiyekan first wondered if there is actually a plan to Islamise Nigeria. Onaiyekan who did not and probably doesn’t think there is such a deliberate plan told Christians: “So let nobody deceive you, I don’t think there is anybody who has plan to Islamise Nigeria, but even if they do, they have every right to do so”. His argument is simple: “They have every right to do so provided they also know that I have the right to Christianise the whole of Nigeria. The answer is not in complaining and crying; stand up like a man and Christianise Nigeria”. He was not done yet, proceeding to add, “People complain that Christianity is being persecuted; they are saying that some people want to Islamise the nation. Just know that nobody can Islamise you unless you agree to be Islamised.

The tougher edge of his homily came in this form: “You don’t Christianise the nation by standing up and looking for prosperity or material benefits. You Christianise a nation, if you are ready to stand up for the truth, preach the gospel, carry the Cross and follow the Lord Jesus”.

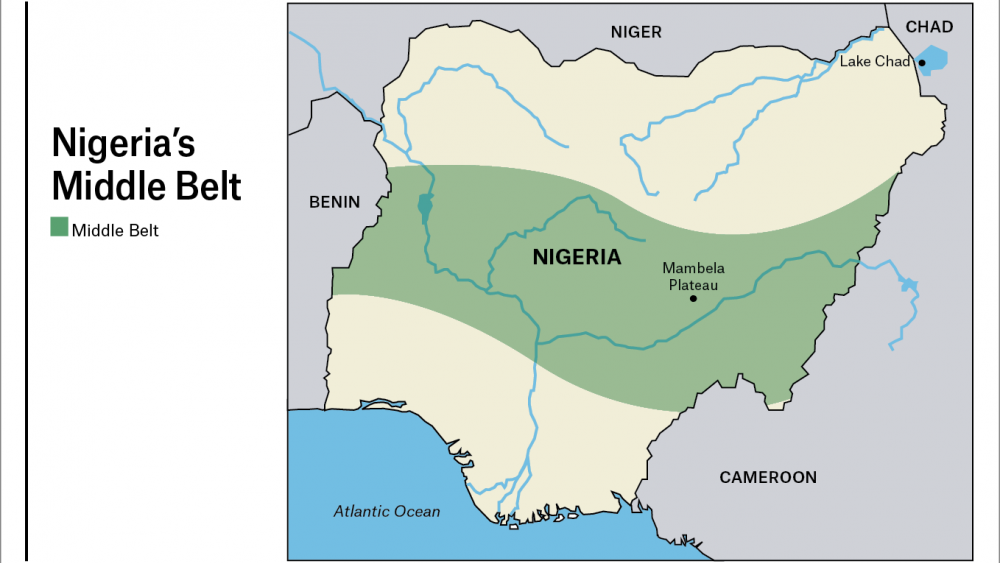

On this account, General Chom Bagu is travelling a beaten path but in a more aggressive manner corresponding to his activist packaging. His anger is perfectly understandable because his region – the Middle Belt – has lost its soul into a victimhood that is re-constituting the region into a zone of unthinking, self-pitying schizophrenics. Life has been reduced to the hype of “the Fulanis are coming”. Even the sight of a Fulani lad with just a cow following him or even some Fulani women carrying Noonoo are invested with being on an Islamisation campaign.

So, General Chom asks, “Is this inferiority complex or Politics?” He continues: We call ourselves natives and cry daily of Islamization/fulanization. We have over the years cast ourselves as the victims. Yet, since I was a baby, I have known that Christian missions are yearly sponsored to spread the good news of the salvation of Jesus Christ. So, the Christians in Plateau cannot in all honesty claim that they are averse to Christianization of Nigeria. Gowon who ruled Nigeria in the 1970s did not feel inferior to command our National troops and lead them to War, JD Gomwalk did not feel inferior to fight the Northern regional government and establish institutions like the University of Jos, Benue/Plateau TV, the Standard Newspapers and withdrew from the Interim Joint Management Board that enabled his cherished Benue/Plateau to stand on its own. Solomon Lar took the North on and funded elections to put a Christian in Government in Niger, Gongola and Benue states. The Aten, even with their Ponies, stopped Amina of Zazzau and the Jihadists from climbing the rocks and conquering the place we call Plateau North Senatorial Zone today. So what has happened to us? We daily degrade ourselves, victimize ourselves and insult ourselves and then expect to be treated with respect. The Hausa/Fulani we so dread and fear are mere mortals, made by the same God. Let us stand up to them not in fearful conspiracies and gossip, but in peaceful competition. If they want to Islamize, let’s Christianize, if they politic, lets politic. Let us match them intellect to intellect, economic prowess with economic prowess in a peaceful way that will boost the Plateau economy within a short time. But please, let us stop this self humiliation and victimization”

Chief Solomon Lar, practioner of ‘Emancipation’ politics many years before the concept came to sum up Marxism for the 21st century

Following Lar or whose footstep as an emerging Middle Belt political leader?

Chom was speaking specifically on Plateau but his intervention speaks to the Middle Belt and even Nigeria as well, caught as these entities are in the current phase of constituting the Fulani as a warlike conquerors and masters in Jihadist intrusion. That is what the current framing game amounts to because of the active verb ‘Islamising’ or ‘Fulanising’. Fulanis are numerically few and highly disadvantaged. Their luck is that intellectually misdirected efforts have successfully constructed them into an all-conquering force by investing them with capacity for fighting and winning. But, language can be reproductive of reality, meaning that Nigeria might be risking the discursive constitution of the Fulani into a power over Nigeria without knowing it.

With even the government talking peace with umbrella organisation of pastoralists, there is no argument anymore about the Fulani identity of herdsmen terrorizing the rest of the country, including the number of people killed and the scale of destruction. The point, however, is that it is one thing for that to be so but a different thing how that reality is represented. Representing it as the return of Jihadism is a self subject-positioning as historically weak and vulnerable group. But as Chom shows, that is not supported by history at all.

The British described General Gowon as an avuncular Christian, a very significant statement. So, why is Gowon’s avuncular-ness and, therefore, his humane disposition even at a time of an all- consuming storm not worth narrating as opposed to how he was used/misused, some of which are made up?

Chom is absolutely correct to say that Chief Solomon Lar set out to install Christian governors in several Middle Belt states. ‘They’ stopped him quite alright even in a place like Benue State where Chief Paul Unongo’s victory in 1983 election was smashed and Aper Aku was declared as the winner. But before that happened, the newsroom at Radio Kaduna had heard of Unongo’s victory, informally though. So, Lar was on the offensive. It was that offensive that made him delegate the flagship programme of his regime – the Emancipation programme – to his Deputy Governor, the equally late Akwe Doma who brought to his governorship of Nasarawa State from 2007 to 2011 huge chunk of that experience. Till today, Chief Solomon Lar is a particularly interesting politician, a puzzle of an African politician who could see in the concept of ‘Emancipation’ the cognitive cover as early as the late 1970s. That is, 12 full years before Prof Ken Booth canonized ‘Emancipation’ as the idiom of radicalism for the 21st century.

And even without Chom’s empirical listing, it has never happened in history that power of the type ascribed to Fulanis would go without resistance to it. Power and resistance go together. So, empirically and otherwise, the representation of Fulani as uncontested conquerors is not only self-humiliating but false. The binary differentiation in that representation is even more paradoxical. The Fulani as all conquering violent intruders presents them as the Other of peace-minded Middle-Belters. But, as there can be no outside without the inside, that differentiation is open to interpretation as a fascination for Fulanis for whatever reasons.

Wherever there is power, resistance is near by

J S Tarka as a case study of resistance within the Northern establishment

It remains intriguing that even some of the best educated Middle-Belters cannot see beyond what meets the eye on this issue. Or, do not accept when it is pointed out that the current manner of framing the Fulanis is a self-vandalising manner of conveying group hurt. Instead, they revel in circulating hysteria on social and traditional media, branding those who do not see any heroism in that as agents or pacificists or such other nonsense. But, educated people have a responsibility to guide their people because that is central to serving humanity. As is generally pointed out, it is not all of us who would become Secretary-General of the United Nations but we still serve humanity if we serve a small component of it.

In the present circumstance, that responsibility would involve letting our communities understand that the world is too diffuse today as to make essentialism dangerous for individuals, groups, cultures and just about every other entity. Even in the current situation, it is still not strategic to frame any one cultural group as one huge, deadly assault squad. And this for three reasons! One, it homogenizes any such group even as it is not possible for the option of violence to have been a shared cultural project. Two, doing so is a humiliating subject-positioning of the narrator to the extent that the narrative subjugates or wipes out the heroism of the narrator even when we know that power and resistance go together and in a relational manner. The danger in that is that the way a group represents itself is the way the world relates and treats it. A group that presents itself as a historical victim, a crying, helpless baby is worth nothing much but pity. Third, enemy images tend to end up in mass atrocity with imponderable consequences even for those who survive such.

There is no argument about it that the Buhari administration has complicated matters by the poverty of its deconstructive politics. Its interventions either came too late or too lame to bring clarity to the argued complicity of the government. Over time, the alternative discourse becomes so consolidated that nobody is ready to shift position from that anymore. This is the problem in all the five most key threats to Nigeria’s stability and well being today.

But the threats are not insurmountable, particularly if it is recognized that Nigeria’s disease is a famine of leaders who can raise the bar of performance. In that context, the way forward lies in more and more democracy and the struggle for its defining elements. Insist on strengthening it. Insist that existing frameworks or models such as rotation of power work. Combat imposition of candidates. Carry out detailed background check of every contestant for the most key offices. Demand qualitative governance. Ask for transformative programmes rather than promises of water and good roads. Those should be taken for granted by now. Make inclusivity a national article of faith. Look down on Messiahs in favour of well structured political parties. Fight corruption, from the local councils to the presidency and insist that votes count at all elections. Above all, build coalitions and let every item of power be negotiated. In all these, note that language can free just as it can enslave or act as a fetter on freedom.

Mr. Onoja, the author, is an Editorial Associate of Intervention