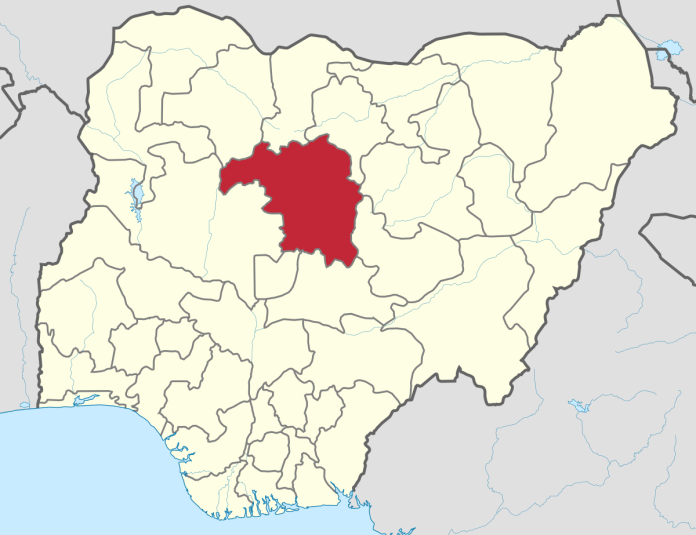

Amidst fears of Kaduna developing into a cauldron with implications for the impending elections, conflict management observers are posing the question of who and how the latest rounds of killings might best be de-escalated. This is more so as, additional to the controversy over the truth or otherwise of the killing of 66 persons of Fulani identity in Maro recently, the police have taken Mr. Dio Maisamari, the president of the Adara Development Association, (ADA) to court but returned him to detention at the State Criminal Investigations Department, (CID) of the Nigeria Police. The leader of the Adara ethnic identity was arrested since Saturday at a Town Hall meeting held by the Kaduna State governor, Mallam Nasir el-Rufai.

Dr Maiwada Galadima, late Agom of Adara

Muslim clerics in the state in a prayer session

Mr Maisamari’s impending trial can only be understood in the context of persistent violence of ethno-religious sparks in the area known as Southern Kaduna since 1981. In the current phase of that, a number of persons of Adara ethnic identity estimated at 11, (eleven) were killed on February 9th to 10th, 2019. It was followed by a reprisal attack in which what is now known as 66 persons of Fulani ethnic identity were killed. Curiously this time, a peace understanding between the stakeholders not to make the killings on both sides public prevailed. Even as concentrated in Kaduna as the more independent minded members of the correspondent chapel, they never got wind of the killings, including the burial of the eleven from Adara community after a funeral service, the sort of thing that hardly escape media attention. And there the matter might have rested with all the risks of the Ostrich approach to it but for Governor Nasir el-Rufai’s disclosure of it on Friday, February 15th, 2019.

While responding to journalists’ questions after some foreign visitors paid him a courtesy call, the governor told journalists of the killings. The government rejected the advice Intervention understood the journalists gave against reporting what the governor had just told them. The journalist, however, relented when the government formalized the disclosure by issuing a statement on it, with all the grissly details. The question is, why did the governor choose the eve of the presidential election to make the information public after keeping it secret for five days? It is from contemplating this question that has arisen the questioning of the authenticity of the story altogether by such actors as the Christian Association of Nigeria, (CAN) and even a government department such as the National Emergency Management Agency, (NEMA) as well as some individuals who posed the question on television.

That is the context within which Mr. Maisamari’s troubles started last Saturday at the Town Hall meeting held by Governor Nasir el-Rufai of Kaduna State at Kasuwan Magani on the latest round of killings in the state. A synthesis of the different accounts from security agents and community contacts show that Mr. Maisamari was arrested and taken to Kaduna from the meeting. Signs that he was in trouble showed up quite early at the commencement of the meeting when he was told to move to a backseat to yield place to some other dignitaries although no strict protocol guided the sitting arrangement as such. It became clearer when, according to the accounts, he was denied the status of a speaker at the meeting and was reportedly told by a commissioner in the governor’s cabinet when he started insisting to “sit down, you are not even supposed to be here”. Another voice also told him “you are part of the problem, you will not speak”. The frightening dimension was the instruction issued by a police officer to those between whom Maisamari was sandwiched after having been forced out of the Town Hall meeting. The security agent was quoted as saying, “In yayi Magana, ku karye mashi kafa” Hausa language for ‘if he talks, break his legs’. In fairness to the governor and his entourage, Mr. Maisamari was not invited to the meeting. He rushed from Kaduna when he heard about it. This is what a community leader who should know told Intervention.

Once taken to Kaduna, he was asked, among others, to make a statement on a communiqué issued by the association sometimes last year. The communiqué in question was the association’s rejection of what it called the balkanization of the Adara ethnic group into Kajuru Emirate on the one hand and Kachia Chiefdom on the other. While Kajuru Emirate is basically two villages with seven, (7) polling units made up of Hausa-Fulani and their Adara ethnic counterpart, Kachia Chiefdom is made up of Hausa-Fulani, the Adara ethnic elements, Jabba and Baju and one or two minorities of minorities. The implication is that Adara Chiefdom had ceased to exist within a programme of realigning chiefdoms by the current Kaduna State Government. The government rationalized the programme as a way of ending the naming of chiefdoms by tribal instead of territorial signification because doing so impinged on the rights and privileges of other smaller identities existing within such chiefdoms, a reality about which the government also claims to have received complaints from those who suffer such status.

Gov el-Rufai, pursuing realignment of chiefdoms

Alhaji Ahmed Mohammed Makarfi who, as governor of the state, pursued a programme of alignment of chiefdoms that is now being deconstructed by a distant successor, Gov Nasiru el-Rufai

The counter-veiling argument from platforms such as ADA is that the same government is creating emirates which contain minorities, mainly Christians. Above all, it is argued that an emirate must be an entity that received the flag from the Jihad leaders, not an emergency entity created by an elected government. And the fact that even under the programme of realigning, other kingdoms such as Jaba, Marwa, Kagoro have been left intact or unchanged. So, while the basis of the government’s idea of realigning the chiefdoms made logical sense, it made no such sense in practical terms, especially when it is perceived that, as presently constructed under the programme, Kachia Chiefdom, for example, would basically become a No-Man’s Land. It did not take long before suspicion of Fulani/Islamisation agenda became part of the story as to be driving the bloody contestation in the area broadly.

This suspicion has been heightened by two major developments, one recent and the other remote. The recent was the kidnap and killing of Dr. Maiwada Raphael Galadima, the Agom Adara, on October 19th and 25th, 2018 respectively. This has particularly complicated matters in the sense that the Adara Development Association, for example, is saying that since the Executive Order which annulled his kingdom pre-dated his death, it meant he had actually been dethroned without even knowing and that his kidnap and death was calculated. The remote reason is the reported removal of the Cross from ambulances belonging to Kaduna State Government and its replacement with the Crescent with the onset of the Nasir el-Rufai administration, an action understood as signifying the much talked about Islamisation agenda leveled against the Kaduna State governor because, according to interested sources, the international best practice is to use both the Cross and the Crescent.

Ethnicity in itself is harmless and could even be emancipatory. As such, the context in which it could become a weapon of offensive or defensive deployment is always what conflict managers look at. For those concerned with de-escalating Kaduna State at this point, the search for and identification of the context warranting the violence is primary. That search for the context of the current cycle of bloodbath in the state has snowballed into a battle of such discursive claims. There are those saying it is a ploy timed to make elections impossible because, as the site of a key market with participants from many parts of the North, the conflict in Kajuru/Kasuan Magani and surrounding areas can quickly transform into a region wide catastrophe. Others say no, it is Islamisation agenda.

Whose version turns out to be correct will depend on the balance of power rather than the facts of the killing in themselves. As such, questions of how many people were killed and by whom would soon become non-issues and its place taken by which camp is more powerful in all its four forms: discourse, structural; institutional and coercion. However, the relationality of power means that unless Nigeria is cued on to a Mutual-Assured-Destruction, (MAD), then Kaduna is where the question of whether it is a case of ethno-religious contestation or a crisis of leadership, power and governance must be posed quickly by all men of goodwill, inside and outside Nigeria. But who would do that now on the eve of an election seen as a make or mar contest and in a historical conflict which has been allowed to fester up to its current phase which started since December 2016?