By Adagbo Onoja

I am assuming that most people who would read this piece know or have heard about Francis Fukuyama and I am proceeding from there to argue that he is not a voice to ignore. The reason for that is simple. His front row seat number is guaranteed among members of the numerous Academic-Institutional-Media (AIM) complexes that Professor Richard Peet talks about in relation to the production of hegemonic discourses that keeps the world under control for the winners. The geographical implication of that is how Fukuyama could be the source of the discourse that could lead to the liberation of Africa, for instance, or deepen her ordeal. So far, Fukuyama has not seen beyond the United States as the symbolic leader of the Western imagination. He even declared flatly that places, identities or cultures symbolised by Albania or Burkina Faso do not form part of what he calls “the common ideological heritage of mankind”

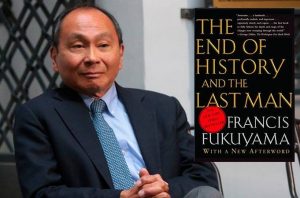

Prof Fukuyama and the book that gave him global voice

So, it matters to listen, read and watch him along with a number of them that can be collectively called intellectuals of statecraft. He talks a lot, writes very much and there is no award for the most provocative scholar in the post Cold War era that he would not be the winner. It would seem that problematising provocatively was a module arranged exclusively for him as a doctoral student at Harvard or even much earlier. His ‘End of History’ argument can be regarded as an exercise in provocative intellectualism. The idea of such claim when the outline of the world that was shaping up in 1989 was still so fuzzy borders on either a major sacrifice for some idea, institution or interest on the one hand or a case of over-confidence of one who does not think of the world much beyond the United States and what it stands for. Interestingly, it did not take long before his thesis was ruptured by a far more interpretative intervention in Huntington’s “The Clash of Civilisations?” which also became a book later. Whatever setback Huntington unleashed on Fukuyama, he made his name in global scholarship by provocatively and, perhaps, carelessly, declaring liberal democracy the winner of the ideological contestation that has circumscribed human history.

In late 1998, he moved over into the controversial argument about the inevitability of patriarchy because the rest of the world outside the west may not be able to accommodate such gender sea change. What comes out is a binary view of the world in which certain parts exist in opposition to certain others. Not for him the overlapping, diffuse world marked by simultaneous integrating and disintegrating tendencies. His capacity for tying data of his choice into tremendously fascinating but problematic conclusions follow Michael Deutsch’s approving quotation of those who asserted absolutist, illiberal tension in liberalism. It works out in an alarmist, hysteric reading of whatever it does not understand as a monster or enemy of satanic proportions. Although Deutsch wrote in relation to the ideological origins of overreaction in U.S. foreign policy, his analysis applies to how Fukuyama reasons. That is still not the critical problem.

The late Waltz

The more critical problem lies in the Kenneth Waltz that is missing in Fukuyama. Of course, Kenneth Waltz is the acknowledged father of neorealism. After Professor Richard Ashley delivered his “The Poverty of Neo-realism” in 1984, the theory could be pronounced dead but perhaps not clinically yet. He wrecked it on all counts. Only the parsimoniousness remained. By the time Keith Krause and Michael Williams came up with an edited book in 1997, whatever was left of neo-realism was further devastated. It was the remains of neorealism that Professor Ken Booth buried in 2005 when he said it was a textbook example of a problem masquerading as problem solver. Calling realism a ‘cold monster’, Booth said it was ever a theory of the powerful, for the powerful which acted as a password into the corridors of power. Some people would not agree with the dating here. They would be right to give Robert Cox the credit for the assault that commenced the wrecking of neorealism. It was in his 1981 essay which one can re-title “The Limits of Problem Solving Theory” without injury to the communication therein.

But the point here is how in spite of all these fire fights, Prof Kenneth Waltz who reformulated Hans Morgenthau’s classical realism into a fascinating but conservative manifest called neo-realism never let anyone think that he never thought out neorealism fully. Till his death in 2013, he responded to almost every attack on his theory, even after the collapse of the USSR. Most readers would recall his 2000 essay, “Structural Realism After the Cold War”. It was a warrior at work at a time it didn’t make so much sense to defend neorealism. Neorealism can be reduced to a theory of how great powers behave in international politics. It doesn’t have much time for small, powerless states it merely mentions in its literature. So, neorealism was a tragic figure with the collapse of the Soviet Union: a theory of power that did not predict the collapse of a great power. But Waltz remained on course. Whatever is neorealism’s fate today, it is not his fault. Glued to a concept of power measured only in terms of military muscles, neorealism has hardly had much to say in the post Cold War world in which supermodels, pop stars, sports icons, advocacy buffs, television presenters, columnists, theorists, writers and imaginative wives of presidents and prime ministers, among others, have cornered such a huge chunk of power, permanently setting the local, national, regional and global agenda as the case may be.

It could be argued that but for more imaginative realists such as Samuel Huntington, the tradition might have gone under when compared to the decade of the 1980s. In the early 1990s, the Neocons thought very little of neorealists. It might b e coincidence but it was not surprising that it is in their magazine that Francis Fukuyama published the essay version of his ‘The End of History’ argument in 1989 before it became a book shortly after the first Gulf War. There is a scholarly message in the example of Waltz. It is that a theoretical statement must be defended otherwise it could suggest that the theorist was experimenting with human beings since all theoretical claims embody implications. If a theory can no longer be defended, then it must be made clear, along with the grounds for that. This is best done by the theoretician who formulated a particular position.

Fukuyama’s new book

Francis Fukuyama is not doing this. Instead, he is writing, making the events on the ground that are further and further contesting his own theory the subject of books and contestations. Exactly a year ago earlier this month, he told The Washington Post how he didn’t have a sense of democracies turning on themselves. As far as he is concerned, that is what he says we are witnessing today. The problem with that confession is still his inability to look beyond the West. If democracy is going forward in the West, it is The End of History for everybody. If it starts dancing funny in the West, then the world also has a problem. The world starts, ends and begins on one spot even though liberalism is about one-worldism, provided all else are republicans though. That is still fine but why would someone believe in such a conception of the world but without thinking holistically about it so as to be able to explain twists and turns, theoretically?

What is playing out is not a small matter. It is the funny contrast between realists and liberals. Realists insist that to have peace, there must be elaborate preparation for war. So, they appear to be war mongers but who, in the history of the US, have always cautioned against war, from George Kennan to date. On the other hand are liberals for whom perpetual war is the credo, always talking about democratic peace even as it is unobtainable. Instead of interpreting discordant developments such as identity assertions in populism, the rise of Trumps, the rebellion called Brexit as evidence that endism is not adding up and is in need of reformulation in the light of crisis of global capitalism, Fukuyama is theorising these in terms of a dysfunctional West. As he heads to a conversation at The Guardian in London on October 14th, 2018, it would be interesting to see him advance the analysis beyond what hard headed critical political economists, Marxist geographers, post colonialists, discourse analysts, critical security studies and post-Marxists have been saying on identity.

The author, a member of the Editorial Committee of Intervention, teaches Political Science at Veritas University, Abuja, Nigeria