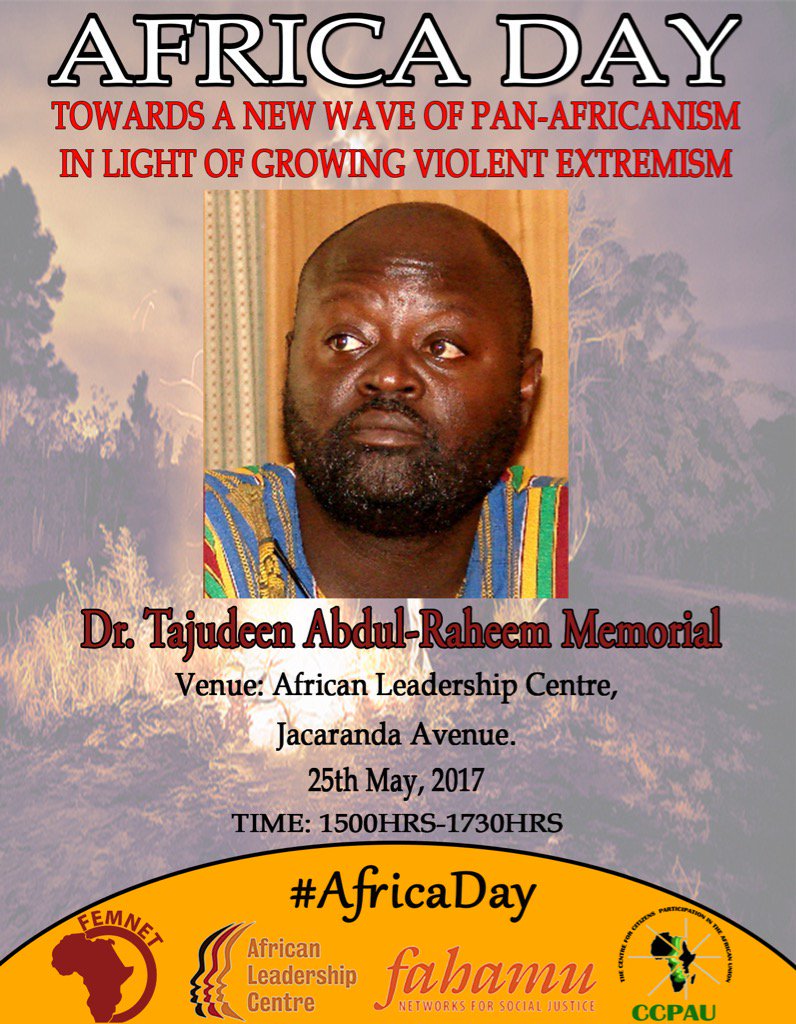

Published originally as “The Taju Challenge” in May 2009 as a tribute to the departed, this piece serves as an appetizer to tomorrow’s inviting surgery on democracy that the Centre for Democracy and Development, (CDD) has put together. But, beyond the substance of the piece, it also lets potential members of tomorrow’s audience into the minds of one of the panellists, Sierra Leonean Professor of History, Ibrahim Abdullah – Intervention

By Ibrahim Abdullah

The powerful intervention in the age-old agency/structure binary that became the thick signifier called Taju

I met Comrade Tajudeen Abdulraheem twenty-three years ago in Oxford, through a Trinidadian comrade, David Johnson, a fellow historian. When I informed David that I will be travelling to Oxford to do research at Rhodes House Library, he suggested I contact Taju, a potential host. Our path never crossed when I was resident in Nigeria, from 1977-1984 but Taju knew almost everyone that mattered on the Nigerian left. Our first meeting therefore turned out to be a Central Committee Indaba that took in more members with the arrival of Adebayo Olukoshi the following day and other Nigerian Comrades. Our discussions principally revolved around the perennial question of la project Africain—what else to talk about?—the left in Nigeria; the struggle against Apartheid; the Africanists scholarly racket;

neo-colonialism/imperialism, and race but hardly Pan-Africanism. This is instructive partly because Taju came from a Marxist tradition that was shaped by the left experience in Nigeria, an experience that is strictly speaking rooted in the history of Nigerian intellectuals and

their romance with the ‘progressive’ faction of the fractious Nigerian Labour Congress (NLC). It is not co-incidental that his first scholarly publication—co-authored with Adebayo Olukoshi—was about the left and the struggle for socialism in Nigeria.

Taju continued to struggle within this tradition when he took up a position as researcher-cum-activist at Ben Turok’s Institute of African Alternative (IAA). The debates then, our debates, if I can call it that, were shaped by an orthodox Marxist project that was informed by classical formulations about history, theory, and society. The short lived Journal of African Marxist (JAM) was anything but African; it published articles written by African intellectuals who

professed Marxist ideas but were far removed from the day to day reality of those for whom they claim to speak. This distance—not just literal and metaphorical—troubled Taju still bogged down with primary research—his dissertation. Time and again he would evoke Cabral as if to remind us all about the monumental task ahead.

By the time he finished his dissertation, Taju had crossed the proverbial Rubicon; resolved to look from within; to explore linkages and potentials within the evolving African community of exiles particularly Ghanaians; and to return to the source a la Cabral. This was the context; indeed the moment of the African Research and Information Bureau (ARIB). And ARIB would become the symbolic signpost between Taju’s self professed Marxism and his discovery of Pan-Africanism as the essential vehicle for the liberation of Africa.

Unlike IAA, ARIB was an African outfit, stitched together by Ghanaian comrades who had been forced into exile by Rawlings: Napoleon Abdulai, Zaya Ayeebo et al. I suspect ARIB gave Taju the intellectual space to think through the African condition in close proximity with battle tested comrades fresh from the barricades with rich experiences to reflect upon. ARIB was praxis in ways that were unimaginable at IAA; it ministered to the needs of the swelling ranks of West Africans in the 90s; and was an intellectual rendezvous for both continental and diaspora Africans. These were extremely hard times when funding was hard to come by and several attempts to cross the Atlantic came to naught.

ARIB was involved in community matters, with race and race relations. The network widened to include Diaspora Africans principally Caribbeans; other Africans also came on board. And before long Taju’s network included the legendary John La Rose and Mzee Babu Abdurrahman, the Zanzibari revolutionary intellectual. Taju became Babu’s protégé; for he would draft him to organize the Kampala Pan-African conference which catapulted him to the continental stage. Before long, Taju was confronted, a la Padmore, with an organizational as well as a theoretical question: PAN-AFRICANISM OR COMMUNISM? Did Taju (re)invent himself as a pan-Africanist to pursue his self-professed Marxist objective of capturing state power? Or did he use Marxism to advance the cause of Pan-africanism?

ARIB was involved in community matters, with race and race relations. The network widened to include Diaspora Africans principally Caribbeans; other Africans also came on board. And before long Taju’s network included the legendary John La Rose and Mzee Babu Abdurrahman, the Zanzibari revolutionary intellectual. Taju became Babu’s protégé; for he would draft him to organize the Kampala Pan-African conference which catapulted him to the continental stage. Before long, Taju was confronted, a la Padmore, with an organizational as well as a theoretical question: PAN-AFRICANISM OR COMMUNISM? Did Taju (re)invent himself as a pan-Africanist to pursue his self-professed Marxist objective of capturing state power? Or did he use Marxism to advance the cause of Pan-africanism?

These two related questions underline the seminal contribution of Comrade Tajudeen Abdulraheem. Like Padmore before him, Taju did not abandon the socialist project. Rather, he skillfully employed Pan-Africanism to advance the socialist project in ways that are not too easy to understand. Unlike Padmore, however, Taju did not make an a priori distinction between organizations on the basis of their alleged revolutionary potential, that is to say, ‘revolutionary’ versus ‘non-revolutionary’ binary.

Taju’s abiding concern was how to creatively pursue the revolutionary agenda even in situations/organizations that are outrightly reactionary or seemingly counter-revolutionary. Which is why he was tirelessly involved in all sorts of disparate liberal activities that on the surface had no bearing to his ideology. Where comrades jettison NGO’s as advancing the cause of imperialism, Taju demonstrated that the reverse is possible if the ideal is solidly grounded on a Pan-African platform; where leftist traditions collectively indict multilateral organizations as imperialist outfits, Taju turned this on its head by making us rethink an alternative trajectory. His abiding faith in human propensity for change against all odds—privileging agency over structure—remains Taju’s seminal contribution to twenty-first century African history. He demonstrated, through tireless practice, that it is possible to humanize inhuman organizations; to neutralize liberal outfits as vehicles of change; and to sell the agenda of revolution without appearing to be revolutionary.

The challenge is how to deepen the privileging of agency over structure so as to advance the struggle for our collective emancipation. This is Taju’s legacy!