The next administration in the United States will be taking over power in a world that is more complex than at any point in US modern history, Vice-President Joe Biden has said. In what appears a farewell essay in the current edition of Foreign Affairs out last Sunday, the VP stated that not even the twilight of the Cold War and the years that followed the 9/11 attacks would match the proliferation of new and old threats as well as challenges, but assuring that “we are stronger and more secure today than when President Obama and I took office in January 2009”. He situated the claimed strength in what he called their investments at home and engagement overseas which he said has positioned the United States in terms of the preeminent global power for decades to come.

Confessing an unmatched optimism about America’s future for the over 40 years he has been in public service, Biden linked this to only if America continues to lead because no other country is better positioned to lead in the 21st century. He, therefore, warns that should their successor decide to turn inward, US world leadership would quickly be proved not to be inevitable.

Anchoring the strength of America on dynamic economy, peerless military, universal values and diplomatic dexterity, Biden recalls a story of recovery to reestablishing the US “as the world’s strongest and most innovative major economy, undergirded by the rule of law, the finest research universities, and an unparalleled culture of entrepreneurship”. He added those to smart investments to thrust the United States to what he calls the epicenter of both renewable and fossil fuels global energy revolution. Biden, however, immediately connected this to the sustenance of the military in which he celebrated US outpacing of competitors, putting that to a defence spending higher than the next eight countries combined. For Biden, the US has the most capable ground forces in the history of the world; an unmatched ability to project naval and air power to any corner of the globe as well as qualitative edge arising from bolstered special operations forces, enhanced cyberspace and space capabilities and investment in unmanned systems technologies.

Connected to specific strides in homeland security, including its associated intelligence infrastructure and the partnership by which they work to abort security threats, the out-going American Vice-President says they all speak to a reality: America’s greatest strength is not the example of our power but the power of our example.

He did not forget to claim credit for the construction of the post World War 11 international order, how well that order has served the US and the world and why they have defend and extended it through arms control and nonproliferation regimes, expanded trade, protected the environment and promoted new norms concerning emergent challenges at sea and in cyberspace. That leaves the new challenges for the US to, in Biden’s words: seizing transformative opportunities on both sides of the Pacific, managing relations with regional powers, leading the world to address complex transnational challenges, and defeating violent extremism.

By his analysis, the US should deepen its relations with dynamic parts of the world, with emphasis on the Americas. Relations with China could not be either or but both accord and discord, he also says. Similarly, Biden articulated a strategy of prudent pursuit of tactical cooperation and strategic stability, on the other with Russia, adding that there was no way the war in Syria would end without DC and Moscow working together.

Biden reveals a watering down of political realism in certain areas of foreign policy by contrasting moral clarity in dividing the world into friend and foe with the demand of “working with those with whom we do not see eye to eye” for progress in international affairs. He exemplified his thesis with the Iran nuclear deal which he insisted is working, aside from peacefully removing what he calls “one of the greatest threats to global security: the specter of Iran gaining a nuclear weapon”.

The rest of the essay dwelt on transnational challenges, defeating violent extremism, admission of home truths about use of military force, among others. This is how Biden ended the essay: There is simply too much at stake for the United States to draw back from our responsibilities now. The choices we make today will steer the future of our planet. In the face of enormous challenges and unprecedented opportunities, the world needs steady American leadership more than ever”.

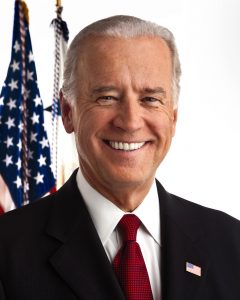

VP Biden: Portrait shoot by Andrew

Byanyima, Exec Dir Oxfam International

Pope Francis

Chinese President Jinping

African readers looking for the continent’s place in the American global gaze would have to read between the lines a lot to find anything more explicit beyond the celebration of American heroism over Ebola and the general statement about deepening relations with dynamic regions of the world. But, what might dynamism mean in the context? In fact, to Nigeria, in particular, is still applied the geopolitically problematic concept of ungoverned space even as the mention of Boko Haram shows reckoning with that threat in American counter –insurgency radar.

However, global security pundits would say this is a major resume of the Obama administration but that as all self-writings go, it contains much of the triumphalist grain in American foreign policy. How much it all reckons with deep rooted crisis of the global order is open to debate. But this crisis has been the subject of considerable attacks of late. Analysts speak of Theresa May, UK Prime Minister’s statement during her campaigns to the effect that “We’re the Conservative Party, and yes, we’re the party of enterprise – but that does not mean we should be prepared to accept that ‘anything goes’,” she said, a reference to unaccountable corporate governance which she specified. This is followed by the inference drawn from the convergence of Bernie Sanders and Hilary Clinton in the struggle for power in the United States. The convergence is interpreted to mean that Mrs Clinton with Bernie Sanders’ identification and acceptance of the research findings that less than one-tenth of the richest one per cent in the United States own nearly as much as the remaining 90% put together. The implication is that income inequality could become global economic governance issue under Mrs Clinton.

Earlier in January this year, Oxfam International alerted the world to how global inequality has reached extremes, with the richest one per cent owning more than the rest of the world does. It posted the inequality crisis as that which global poverty is all about. Oxfam’s position is also a fundamental aspect of the anti-globalisation movement pitching global civil society against global capitalism across the world.

Penultimate week, Pope Francis had said that “a world economy that worshiped the “god of money” and drove the disenfranchised to violence is responsible for transnational terrorism”. The Wall Street Journal, the US newspaper with arguably the most elaborate and powerful rendition of the papal interview in question and the source of the above quotation further reported Pope Francis as saying Islam shouldn’t be identified with violence, suggesting instead that the social marginalization of Muslim youth in Europe helped explain the acts of those who joined extremist groups. That position obviously challenged the dominant narrative of terrorism in terms of Islamic fundamentalism and the question has been whether there is more than meets the eye in the papal intervention.

Put together, these suggest an emerging consensus that contemporary capitalism is now badly aged and due for replacement by a fairer and more equitable variant or mutation of it. The Pope’s intervention is feared to have added the moral voice to the rapping of contemporary global capitalism both by emerging economies, the global civil society and even established bastions such as the UK and US as seen in Theresa May’s statement and the Bernie/Clinton convergence. All of these tend to suggest an emerging consensus that the contemporary global capitalist order might finally be in danger of being dumped for a new variant that is fairer and more equitable.

Analysts point to the impossibility of neglecting the Pope’s views. Nobody associates the Pope with being an ally of communism which The Papacy resisted wherever it touched on the fate of Catholics. It was in one such protest by The Papacy that Joseph Stalin, the then Soviet leader asked if the Pope has got the military capacity to endure a test of strength. Of course, the Pope has no troops in the military sense but The Papacy or the Pope has got the power of discourse, the moral authority, a global constituency and the political status of a Head of state as to awesomely powerful.

As much as it is acknowledged that interpreting the Pope is not an all comer affair, the view in some quarters is that the Pope is informed about the world. He would not go about making statements that would not serve the cause of peace. In this context, his attack on global capitalism instead of Islam in the explanation of terrorism must be informed by what he knows. And if he was being frank about the state of global security, it is a frankness that he must think could push towards a more peaceful and better world. Those who hold this view link it to what they consider to be a proof of it in the wide coverage given to the papal remarks in most global media outlets. Without dismissing it, they think the coverage goes beyond just remarkable demonstration of the tradition of commitment to the media as a market place of ideas.

The G20 which is now the engine room of the global economy is scheduled to meet later next month in China. Might the impending meeting accomplish a dramatic deepening of the reform of global capitalism which it has already started with the stalled reform of the IMF, particularly in the light of impending US Congress ratification of the quota aspect of the reforms?