By Adagbo Onoja

It wasn’t a seminar. It was a social outing except that all the attendants have social science background. In fact, all but one of them are political scientists, invited to share the evening. What else but politics, Africa and its tragedy of transgressions against it would dominate in such an informal diplomatic interaction at an Abuja popular culture site?

At this point, let’s permit a sharp diversion to commend the mastermind(s) behind the creation or emergence of this culture of scholars, friends and activists forming an irregular, evening-sharing session over cholesterol-free delicacies, a ritual which now completes the cycle of interaction of visitors to Nigeria, thereby breaking the rigidity of the formal/informal diplomacy binary.

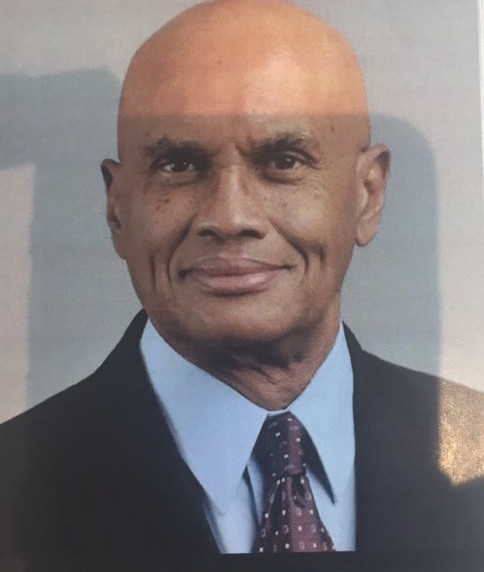

Back to our topic of the day. Politics could not but dominate the evening, not when the guest of honour, as it were, was Prof Richard Joseph, one of the pioneer American political scientists who chose Africa/Nigeria as their subject of specialisation. Amongst others, they include Crawford Young, Larry Diamond, Robert Jackson, Peter Lewis, Jean Kirkpatrick, Carl Rosberg and Richard Joseph.

Back to our topic of the day. Politics could not but dominate the evening, not when the guest of honour, as it were, was Prof Richard Joseph, one of the pioneer American political scientists who chose Africa/Nigeria as their subject of specialisation. Amongst others, they include Crawford Young, Larry Diamond, Robert Jackson, Peter Lewis, Jean Kirkpatrick, Carl Rosberg and Richard Joseph.

Of these, Richard Joseph has an attractive stature. Not only has the NIIA just found it worth naming a learning centre after him, he is, of course, the scholar who applied the theoretical concept of prebendalism to Nigerian politics in the aftermath of the crash of the 2nd Republic. In those days (up to the mid -1990s), it was impossible to graduate in Political Science in Nigeria without reading Democracy and Prebendalism in Nigeria by Richard Joseph along with all such narratives of Nigeria/Africa at the time. Peter Lewis was another of the interesting American scholar of Nigeria then, a subject of contested appraisal in the then more vibrant Nigerian academic community, what with his titles such “From Prebendalism to Predation: The Political Economy of Decline in Nigeria” or his “From Prebendalism to Sultanism: The Political Economy of Decline in Nigeria” and so on and so forth, even to this day.

So, sitting with Richard Joseph this evening a week or so ago at a time when some of the titles of academic essays under reference are seeming unfolding as predicted reminded Intervention of one of the paradoxes of theorising. A theorist helps clarifies a problem, with particular reference to the power relations every theory strengthens or weakens. That’s why it remains a consensus in political science across the Atlantic that every theory is for someone and for some purpose.

On the other hand and flowing from the partisanship of all theories is the (unintended) complicity of every theory in the consequences it is performative of as a discursive structure. As such, the first question one had in mind at an opportunity to share an evening with Prof Joseph was how he is thinking about this paradox for which the social science community has no solution to date. As scholars and researchers, we must theorise. We do this every now and then through the essays, book chapters, books and popular culture outputs we produce and each of which contributes somehow to strengthening or weakening an existing power relationship. As it is power rather than class or any such deterministic category that determines what counts, all theorists fuel or undermine something somewhere all the time.

Unfortunately, the evening unfolded in a way that made this question impossible until it was too late. It was posed quite alright to a Prof Joseph who appreciated it but who could only promise to get back to Intervention later because the car taking him to his hotel had already arrived. What consumed much of the evening was Prof Joseph’s scholarly perceptiveness in relation to the timeless topic in African politics – colonialism.

Unfortunately, the evening unfolded in a way that made this question impossible until it was too late. It was posed quite alright to a Prof Joseph who appreciated it but who could only promise to get back to Intervention later because the car taking him to his hotel had already arrived. What consumed much of the evening was Prof Joseph’s scholarly perceptiveness in relation to the timeless topic in African politics – colonialism.

The point that Prof Jibrin Ibrahim started off with in the evening is the recent report of French role in colonising Cameroon, commissioned by the two countries. The report was submitted late January 2025. It is the outcome of President Macron’s politics of writing France back into Africa which he launched in mid-2022 when he undertook a tour of about half a dozen such countries. At a press conference in Cameroon in the course of the tour, he stressed France’s determination to fully re-open France’s archives on colonial rule in that country, with historians from France and Cameroon to investigate what was called “painful moments”. It is a move Frank Gerits, the University of Utrecht’s Historian of International Relations describes as a strategy of penance for colonial crimes, albeit a stylish strategy of colonial re-assertion.

So, the 2025 report is within that framework, notwithstanding the so much water that have passed under the bridge between 2022 and 2025. France has basically been expelled from West Africa, what Intervention would call a classic case of decentering from a historical primacy although there is the expressed French optimism to regain primacy in (West) African affairs in a matter of half a decade. Whether it will work that way remains to be seen.

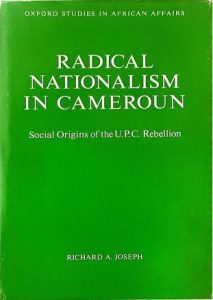

But what makes the report interesting or what must have moved Prof Jibrin Ibrahim and others gathered this evening must be how Prof Joseph had already published a book on what the French did in Cameroon as early as 1977 regarding containment of radical nationalism against it. It means a ‘convergence’ in meaning between what Joseph did decades ago and what the French are doing now. Intervention does not know what this contributes to in other traditions of scholarship but it will quickly throw up the concept of Diffarance among those who subscribe to Derridean Deconstruction. By Diffarance is simply meant that no objects or events or practices derives its own meaning from qualities inherent in it but from what it is not (difference) and from other practices or events it must defer to. In 1977 when Joseph published his book, it was most likely regarded as prying in to what should be forgotten if not what was unnecessary. Today, the dynamics have worked out in such a way that prying into how France crushed nationalists in Cameroon is a strategy for possible revival of French primacy in former French dominated (West) African countries.

The cover of the 1977 book

So, even if Prof Joseph stopped at just publishing that book, he has established his place in scholarship by making a substantial contribution to the theory of meaning as Derridean Deconstruction understands it. Although that’s not what he might have set out to achieve when he wrote the book, not being a Deconstructivist scholar, that doesn’t matter since intention is not a subject of critical scholarship in the analysis of meaning.

The second indirect contribution his book embody is whether France can regain West Africa. It is an issue on which opinion is certain to be ‘no’ in many quarters especially within the region. There are other quarters where the opinion is certain to be ‘yes’. Well, none of such opinions would be right or wrong. Of course, France can regain West Africa just as France may also be pursuing illusion. It will all depend on who defines the word ‘regain ‘ in this context and which camp more quickly constructs and naturalises its own notion of regaining into the consensus/consent of all parties concerned. It is only such hegemonic consensus that will determine winners and losers.

Let’s contemplate a particular case. Without a continental army that can enforce peace, given what the M23 has made of SADC peace enforcement troops in the DRC, why won’t France turn up as the benevolent Leviathan tomorrow should anarchy break out in Cameroon in the event of President Paul Biya’s demise? (Even as Intervention prays for him to live longer, it is no longer anything a terrible thing to say that, at 96, Biya has less days on earth than he has already spent).

So, the case for thinking of reality in terms of contingent, relational interpretation would be argued to have been made in the ‘convergence’ of meaning between Prof Joseph’s book and the current French move. Prof Joseph’s book is not too singular to bear the burden of that inference. If meaning is never a fixed, permanent stuff, what should that mean for our sense of politics? Employ ‘our’ as a shifty-shifter here, it means I am referring to Africa and the imperative of it mastering how to be a winner by moving from meaning in arithmetical, statistical, fact and figure direction to articulatory practice or what Achille Mbembe calls the practice of turning facts into signification. Articulatory in this sense has nothing to do with languaging or grandiloquence but the production of power through the politics of meaning.

It was an interesting evening, what with some of us learning how to pronounce Achille Mbembe in a manner that his mother would know it is the Cameroonian philosopher we are talking about. But, more than that, the evening means that a major American scholar of Nigerian/African politics did not come to town and there was no conversation. Abuja may have no Abuja Review of Books similar to London, New York, California but it has Abuja Review of Fish Joint Conversation. Who knows whether it may not metamorphose into an Abuja Review of ‘Books’?