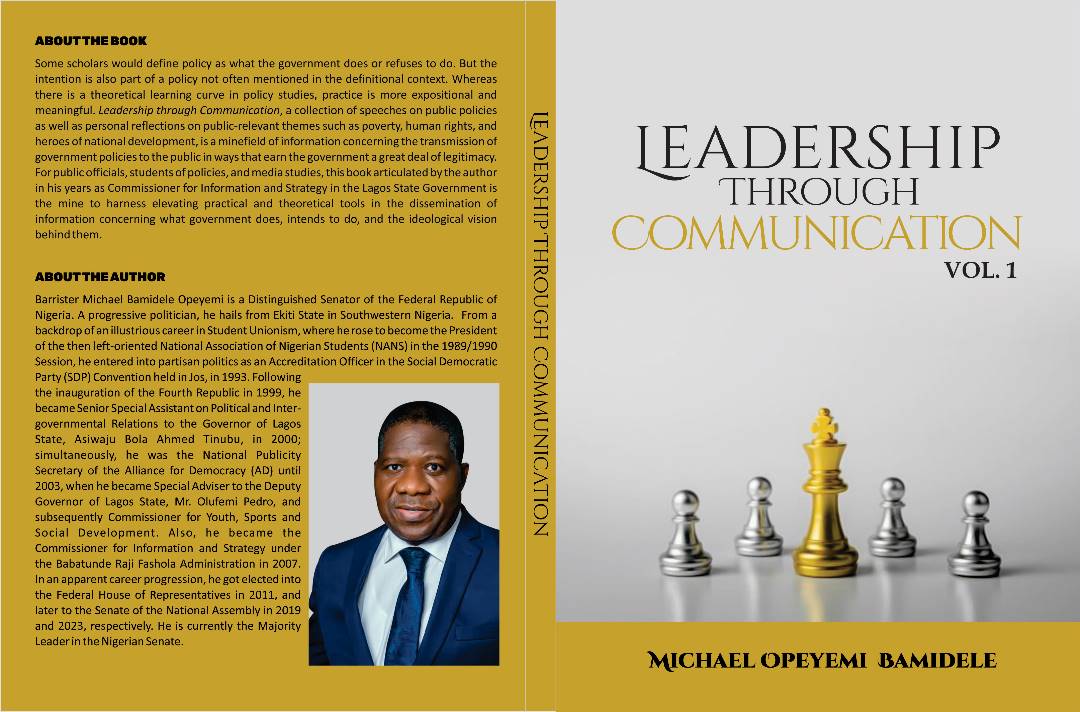

In December 2022, Mallam Salihu Lukman, a former president of the NANS that Nigerians know, turned 60. On July 25th, 2023, it was the turn of Bamidele Opeyemi, another former president of NANS of those days to turn 60. Might a layer of politicians with a definite root be emerging in Nigerian politics? That is a question for another day while we turn to this review of Senator Bamidele’s self-reporting on his stewardship by way of a book. Interestingly, it is to another NANS leader of that generation that we meet in this review. That is Sylvester Odion – Akhaine, a Professor of Political Science at the Lagos State University. Enjoy the piece!

Leadership through Communication, in two volumes, is an interesting read. It brings to the surface an intellectual problem that should deserve our attention. It raises the question of whether an individual who is a public official, in this instance, a Senator, can become a public intellectual. I shall briefly address this in what follows.

Edward Said argued in his 1993 Reith Lecture that it is difficult to draw a line between the public and private intellectual. As he puts it, “There is no such thing as a private intellectual, since the moment you set down words and then publish them you have entered the public world. Nor is there only a public intellectual, someone who exists just as a figurehead or spokesperson or symbol of a cause, movement, or position. There is always the personal inflection and the private sensibility, and those give meaning to what is being said or written.”

On his part, Paul Baran draws a line between the intellect worker comfortable with the status quo and the intellectual whose core attribute is the desire to tell the truth. In his words, “The desire to tell the truth is therefore only one condition for being an intellectual. The other is courage, readiness to carry on rational inquiry to wherever it may lead, to undertake ‘ruthless criticism of everything that exists, ruthless in the sense that the criticism will not shrink either from its own conclusions or from conflict with the powers that be.’”

In this connection, the intellectual is “a social critic, a person whose concern is to identify, to analyse, and in this way to help overcome the obstacles barring the way to the attainment of a better, more humane, and more rational social order.”

In this connection, the intellectual is “a social critic, a person whose concern is to identify, to analyse, and in this way to help overcome the obstacles barring the way to the attainment of a better, more humane, and more rational social order.”

The notion of the public also needs clarification. There is the general public approximating the society as a whole, a discursive sphere with contending social classes, and the public which inheres in the officialdom “consisting of middle and upper class policy makers, administrators, and professionals…” (see Ellen Cushman, 1999). This is the sphere to which the author belongs. He has crossed into the public sphere with an overly concern for human well-being and progress while simultaneously retaining his status in officialdom. This raises some tension because he has not committed class suicide. However, class belonging is not determined by outright suicide, that is, exit from the privileged class since there are other forms of identification with the oppressed class in society. Firstly, class consciousness inclines one towards identification with the exploited in society. Secondly, practical actions to liberate the oppressed. Thirdly, class solidarity with the oppressed through shared experience. The above is the preface to understanding Leadership through Communication articulated in two volumes.

Volume One, an agglomeration of the speeches of the author while he was a Commissioner for Information and Strategy in the Lagos State government, can be divided into three parts. Firstly, it focuses on the agency of the media in promoting public policies in theory and practice. Secondly, there is a preoccupation with the downtrodden in the society. And thirdly, an evaluation of the defenders of our common good.

In furtherance of the agency of the media, especially government information agencies in national development, the author explores the role of the media from a historical perspective dating back to the anti-colonial struggle and anti-military struggle within the matrix of social responsibility. He holds the view that there is a need for synergy between government information agencies and the mainstream media in the task of nation-building through constructive criticism and feedback. The author ties this up with the importance of communication in achieving development at the grassroots, the latter being about the people. This calls for a communication strategy that combines traditional interpersonal communication methods with the modern that is both vocal, digital, and symbolic.

The author goes further to underline public relations as the engine of re-branding the nation given its negative image. Conscious of this, the Lagos State Government which he served, supported the National Institute of Public Relations and re-engineered governance in other to bring succor to the people. For him, the role of Public Relations professionals in re-branding the image of Nigeria, making it a haven for investors cannot be overemphasised.

Exploiting the ex-cathedral space given by the Young Men Christian Association, the author foregrounds the rights of man, drawing on the philosophies of the Enlightenment period, a la Rousseau and Locke, and the travails of human rights in World War I and II, and the corresponding evolution of supranational institutions for the protection of the rights of man. In this historical excursion, the author articulates Nigeria’s experience of rights violations traversing the civil war years and the last military dictatorship. Also, he acknowledges the consequent struggle of civil society to overcome violation that is at one with God’s commandment.

The subject of June 12 and the attribute of Chief Gani Fawehinmi provides the author with a reflective space to articulate the struggle for the common good of Nigeria. Nigeria’s modern history is incomplete without the mention of the place of June 12, the day in 1993, when a free and fair election was annulled by the military. Many Nigerians bore the brunt of the struggle for the realisation of the June 12 mandate. The list includes Chief M.K.O. Abiola, Pa Alfred Rewane, Alhaja Kudirat Abiola, Bagauda Kalto, and other martyrs and unsung heroes of that epic struggle. The author calls for their immortalisation.

Public official as public intellectual!

In the struggle for human rights in Nigeria, Fawehinmi was a colossus. The subject did not only handle over 5000 cases in the Supreme Court but equally dealt with more than 2000 other cases in varied courts of competent jurisdictions. In articulating the struggles of Fawehinmi, the author provides a matrix for future biographers. All these issues dovetail into the ‘rightfulness of the unit’ of the Nigerian state, which the author addresses under the rubric of federalism. He avers that the contradictions of the Nigerian state have continued to hobble the realisation of the dividends of democracy in ways that make political party promises mere slogans. For him, the solution lies in a return to genuine federalism in ways contemplated by the Lyttleton Constitution of 1954 where a great deal of fiscal autonomy was engrossed.

Importantly, the author engages with the question of poverty through the prism of his ideological orientation. The well-known statistics are cited. For him, the causality lies in the kleptocracy of state actors and the neoliberal market policies of the Bretton Woods Institutions. His prescription lies in national self-reliance and African integration.

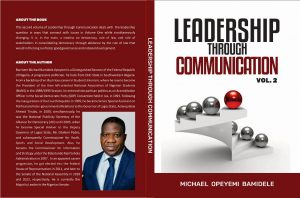

Volume Two is a treatise on democracy and its components, namely, the rule of law and stakeholders’ responsibility. The contribution of the late Dr. Frederick Fasehun, Pioneer Chairman of the defunct Labour Party and Founder of Odua Peoples Congress, to the growth of democracy, provides a vent for the author’s review of Nigeria’s democracy.

Against a backdrop of democratic cynicism and relegation of efforts of pro-democracy activists, he traces the origin of democracy to the classical era of the Athenian democracy with a selected franchise and concludes that democracy is about faith in the people in ways that affirm the authoritative assertions of David Beetham’s conception of democracy as a rule-making process over which the people exercise control. In what follows, the author underlines the contradictions of Nigeria’s democracy, namely, flawed transition, authoritarian temptation, hounding of opposition, elimination of dissent, extreme poverty, corruption, and consequential instability.

However, Bamidele acknowledges efforts being made to remedy the situation that includes the amnesty programme in the Niger Delta. Subsequently, he calls for faith in government while urging increased political participation, strengthening the rule of law, and resolving the skewed federal structure of the Nigerian state.

The rule of law received particularised attention, an assertion of the professional forte of the author. For him, the rule of law is the core of democracy, and it is to be preferred over the rule of men as John Adams, a former President of the United States once put it. To be sure, an impartial judiciary with legal practitioners is the bastion of the justice sector and democracy. As Justice Timothy Oyeyipo, former Chief Judge of Kwara State has rightly noted, “The administration of justice is the core of any successful democracy in the world. If the Legal profession fails, anarchy will be the only beneficiary.” Besides, it is argued that lawyers as critical stakeholders who must keep vigil over democracy and the human rights of the citizens. It is their professional commitment. Sapara Williams, the doyen of the Nigerian legal profession, once noted that “legal practitioners as moral agents live for the direction of people and advancement of the course of the country. Chief Fawehinmi makes this role more compulsive. As he puts it, “if you deny the people economic rights, you enthrone poverty, and by that, you misdirect the people, hence agitation for social justice for the people.” the author notes that in the democratic project, we are stakeholders. In this regard, the civil service, the integrity of state actors, and civil society’s engagement with state minders are all invaluable to the consolidation of Nigeria’s democracy.

In the beginning, I mentioned the issue of tension that exists in the position of being a public official and public intellectual. The author runs away from the problematicisation of the law as a class instrument which a positivist interpretation will lead, and tread on the path of a reformer in a system that requires an overhaul. Another structural discontent is the author’s struggle between the official mode of communication and the gilded style of academics. By refusing to stay in one spectrum, the official, missed the spontaneity and poetic license of public performance. Nevertheless, Senator Bamidele holds the beacon for all public officials to ventilate the workings of their minds. The Nigerian people need to know what and how their political leaders think and act.

Finally, the book under review provides the reader with a binary advantage. One, it offers insight into how to navigate the policy environment while securing the acceptance of the people. Another is the seminal contribution to the principles of democracy and the rule of law. It is to be noted that the book has other supplementary subjects such as youth, Lagos mega city, and education, that would be of interest to the readers.

Leadership through Communication by Senator Michael Opeyemi Bamidele, published by Amicus Law , Lagos & Abuja, Nigeria, was presented in Abuja on July 25, 2023.