A few hours from now, it would be four years since Prof Abubakar Momoh bided the world good bye. The belief that the social is discursive rather than foundational carries with it the responsibility to, in any small ways possible, keep an Abubakar Momoh a regular subject of the conversation. It is in doing so that an even clearer meaning and significance of the late professor of Political Science can emerge. But, as was said of the equally late Bala Mohammed, Political Adviser to Governor Mohammed Abubakar Rimi of Kano State in the Second Republic, so should it be stressed that Abu Momoh is not significant because he was a professor. He was also not significant because he was an ideologue, of whatever persuasion. Some people would put his significance in a powerful ideology of raising the bar. In fact, it would seem that, with Momoh, almost anyone can get away with murder if s/he has set a record.

One of his works along with one of his coleagues then at the Lagos State University, (LASU)

He tended to worship excellence, particularly academic excellence. There can hardly be a better illustration of this claim than this story, irrespective of how many times it might have been told before. One had gone to his office at The Electoral Institute in the first few days of October 2016. As what brought the visitor was over and it was time to depart, Momoh asked the visitor if he knew Prof Adigun Agbaje, the University of Ibadan Political Scientist. Yes, came the reply. But the yes did not appear to carry the enthusiasm or stress on Prof Agbaje that he obviously expected to hear. So, he asked the visitor to sit down, taking his time to introduce Agbaje to this visitor of his who did not appear to him to be sensitive enough to the fact of an Agbaje who made a First Class in Political Science when Nigeria was still working.

It wasn’t that the visitor was ignorant of Agbaje’s feat. It was rather Momoh’s own worship of excellence that was playing out. It was his own dosage of the spirit of insisting on raising the bar in whatever we do. He could argue against any manifestation of mediocrity or what he considers to be so, taking upwards of an hour or more to lecture on why his ‘victim’ does not deserve to be in the category of the mediocre.

Written works attracted his sternness against perceived mediocrity most. In one instance, a draft stuff was sent to him. He took his time to read it, returning it with this comment, “I know you will agree with me that you are no longer “speaking in tongues” and neither are you “swallowing” what you were meant to express in writing”. In another instance, he wrote as follows, “Somehow, your work is making a persuasive intellectual (rather than journalistic) argument for itself. I am sure Prof. Osaghae will be happy with you now”.

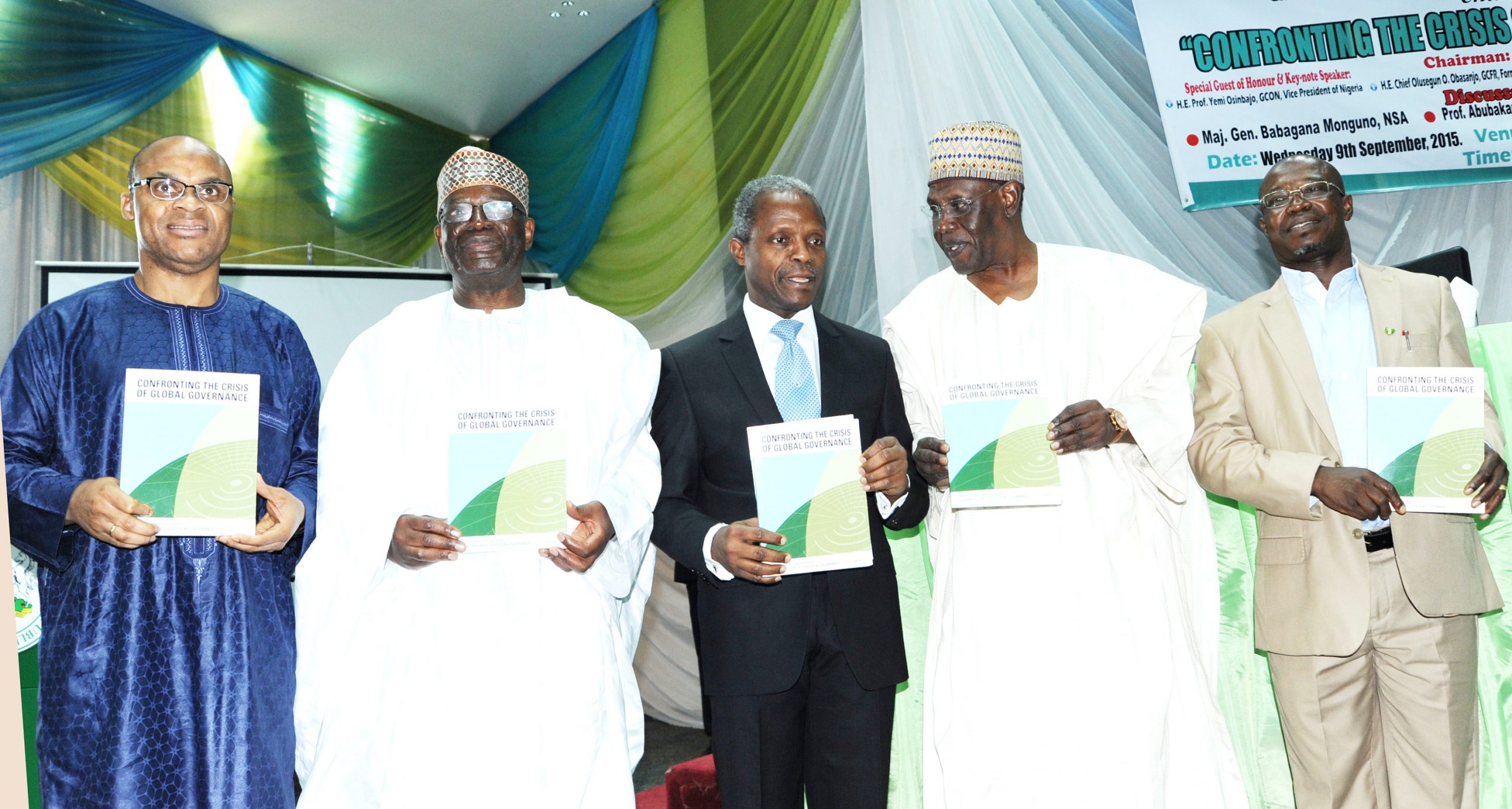

How it was for the two of a kind then

But he was quick to recognise whatever he considered as improvement and in such cases, he could begin his comments with “Oga Onoja” or oga anybody even though the text would not go far before he kicks at signposts of what he, again, considers to be less than magisterial. An example was when he returned a different stuff with the following comments: “Kindly find attached what you sent. I believe the Chapter was rushed. It can be made more methodical, elaborate, coherent and explicit. Reflect a little deeply on the issues raised and see how you can make it more poignant and majesterial; especially from the section where you began to engage “Critical Content Analysis”. And so on and so forth.

He stressed any PhD student who missed his way into him. As far as he is concerned, a PhD maybe awarded by a particular university but a PhD is not of any university. This is the consensus but Momoh will re-communicate this in a way that gives the issue a different weight.

The long and short of it is that Abubakar Momoh was as academic if not more academic than ideological. He would say that Marx would not be a case study in social theory if he were merely polemicising. And he would go on to stress the amount of empirical work that went into the theoretical claims Marx put on the table and which makes his interventions in social theory substantially referential. So, he could afford to say something like, “I don’t care what conclusion you are pushing but I care about how you arrived at that conclusion”.

Was he, therefore, a post-positivist? That could be difficult to answer because, although he did not believe in foundationalism or linearity, he did not formally proclaim a methodological commitment to interpretivism. But his language use, particularly his attack on territorialisation of identity, marks him out as a post-positivist. And he never attacked anyone or displayed any hostility to post-structuralism. In fact, it was his ‘live and let live attitude’ to that which informed the statement about not being worried with one’s conclusion but worried about how the conclusion was reached. As in the academic dimension of it, so it was in his praxis. A critical look at his own PhD thesis is most likely to reveal him as actually a post colonial theorist which is what most of us are even as we proclaim ourselves as Marxists in the orthodox sense of it.

It would be difficult to finish writing about Momoh in one piece, no matter how restricted an angle one takes. All those who benefitted from his generous time for knowledge transfer can do is, perhaps, to keep taking a small part of him at each anniversary of his death. Covid 19 and the generalised insecurity in Nigeria today might have made it impossible for any elaborate memorial at the 4th anniversary of his passage as has been the case in previous years. But tomorrow might be another day!