Would the quality of education in Nigerian universities be raised by mobilising and injecting Nigeria’s reserve force of well heeled professors and senior academics who have left the system formally but are still capable of, individually and collectively, making a decisive contribution to the re-making of education in Nigeria?

This is the question on a considerable number of lips now partially in response to the spate of grudges against the system recently. A prominent Vice-Chancellor told Nigerian undergraduates recently to leave Facebook and face their books. The Nigerian government is complaining. The World Bank complained much, much earlier. Even the regulatory agency –the National University Commission, (NUC) is threatening a reform whose dimensions no one knows yet. All of them are raking against the university system, particularly on the overall quality of education.

Prof Mike Adikwu, VC of FG own University of Abuja and proponent of the postdoctoral research strategy

So, haven’t the dynamics worked out in such a way that it is time to construct a pact between the Nigerian government and Nigerian academics who are though formally retirees from the system but can be pulled back. Pulling back the category of retirees into the system has been reinforced into currency by the recent argument of Professor Michael Adikwu, the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Abuja that there is no other way to resolve the crisis of quality in the university system other than an aggressive pursuit of the postdoctoral research strategy as opposed to the illusion of dealing with the crisis from below. Critical observers of the system are thinking that it is even the starting point of the Vice-Chancellor’s proposal because the entry of that quantum of well versed elder academics prepares the ground for producing PhD materials that can go out and engage the system while also increasing the quality and quantity of PhD products domestically and immediately.

The argument is that these professors and senior academics are all very much available, the engagement can be immediate and the resources required to put them to work is minimal. They are not going for battles for Vice-Chancellorship, HODs, competition for research grants and any of those things that creates tension on campuses. They are not on the wage bill of the individual universities and there is no university that cannot find offices for its own quota of that pool. At 164 universities, it is very unlikely that each university would get more than two, depending though on what formula for sharing is approved.

Above all, the idea is argued not to be that strange after all. The late Prof Takena Tamuno was around and about at the University of Ibadan and even writing and publishing almost till he breathed his last. At 80, the late Prof Abiola Irele was still teaching at the University of Ilorin before his death. And even now, there are those such as Professors Asobie, Toye Olorode and Dipo Fashina still teaching, one way or the other, after retirement. Prof Biodun Jeyifo spends his time between the US and Nigeria. He can be doing something on a Nigerian campus each time he is around. So, the Nigerian government can pull back most if not all retired academics in and around the country to contribute to managing what is believed to be some kind of emergency in the university system, if the range of people complaining about the system is anything to go by.

These are no ordinary academics. Most of them have gone to the best schools around the world. If you take those that emerged as leaders of the ASUU, Biodun Jeyifo went to Cornell University, Mahmud Tukur to ABU, Zaria, Asisi Asobie to London School of Economics, the late Festus Iyayi to Kiev and later Bradford in the UK, Attahiru Jega to Northwestern University, Dipo Fashina to the University of California, Los Angeles and so on. There is nothing like the best university but these are some of the most outstanding elite universities in the world. Even people who knew Prof Asisi Asobie long before now were awed when his citation was read at The Electoral Institute’s First Abubakar Momoh lecture last Thursday. And that is what one finds with most of them in that generation. So, why would such collection of people who are sound, committed and available not be pulled back and injected, goes the question.

Igbinedion University, Okada’s Prof Eghosa Osaghae, VC with awesome CV

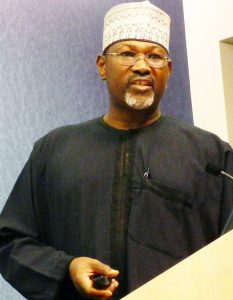

Prof Attahiru Jega, experience spanning ASUU, VCship, INEC Chairman

Such a list would stretch from those who have completely retired but are not tired; those who are either on the verge of exit from the system or are serving as Vice-Chancellors and might not move into other things but can still assist the system somehow; the category that are not currently teaching because they are on government service but are irreplaceable and, finally, there are those in NGOs who are, nevertheless, mobilisable. A sampler of the list across the different categories would stretch from Professors Enoch Oyedele, Okello Oculi, Y.Z. Yau, David Ker, Asisi Asobie, Egite Oyovbaire, Isawa Elaigwu, Yakubu Aliyu, Bolaji Akinyemi, Adiele Junaidu, Idowu Awopetu, E. R Ajayi, Moses Ola Makinde, Soji Amire, Kola Torimiro, Prof Dandatti Abdulkadir, Oga Ajene, Tony Edo, Mike Kwanashie, Eghosa Osaghae, Alli, Alemika, Alubo, Sule Bello, Nuru Yakubu, Toye Olorode, Dipo Fashina, Sonny Tyoden, Jibrin Ibrahim, Alex Gboyega, Bayo Adekanye, Okechukwu Ibeanu, Sam Egwu, Ogaga Ifowodo, Adebayo Williams, among many others that cannot be recalled immediately. It is difficult to place Yusuf Bangura on the list.

Some people estimate that no less can 2000 can be compiled. The assumption is that Vice-Chancellors would be disposed to such an arrangement, especially those of some of the new, private universities that are most conscious of standing out from the crowd.

There was a time they were chased around mainly for “teaching what they were not supposed to teach”. This was the ‘crime’ the state imagined them to be committing and which was framed as such by the late General Emmanuel Abisoye, one of the most sophisticated intellectuals of the Nigerian military in his time and who was head of government investigation into student uprising in Ahmadu Bello University in the mid 1980s. On its wisdom, the state went after ‘them’, mostly those in the leadership of the Academic Staff Union of Universities, (ASUU). Today, the government itself is in the forefront of complaining that the university system is not performing its role to the state and that university workers were right in their perspective of the crisis. It is in that context that some stakeholders assume that government is most likely to look into Professor Adikwu’s argument, he being the VC of Nigeria’s capital city university. But even if government accepts the idea and finds the money, how soon can it produce outcomes without an emergency measure such as injecting tested and untainted academics?

Their presence, it is argued, would be a mentoring system in itself. “Their mere presence on the corridors of Departments means that certain things wouldn’t happen, younger academics would get the benefit of solid processing and they can best handle certain core courses such as theories and methods, especially at the postgraduate level”, it was argued. The clincher appears to be the question as to whether anybody would say that there wouldn’t be a big shift if Nigeria can inject 1000 solid academics into the system today, meaning that they would be coming as guides, especially in designing the courses which some academics say is more crucial that delivery of courses.