Reading Gusau and Ile-Ife Flash Points

Brig-General Suleiman Zakari Kazaure, DG of the NYSC scheme

Two of the headlines these past few days regarding an assault on a serving corper in Gusau in Zamfara State and inter-ethnic clashes in Ile-Ife in Osun State are bound to leave many frustrated. Without going into details, these flashpoints would suggest to many the rising threat of official and unofficial lawlessness in the provinces in particular. As such, they are worrisome because they are some of the small events that could trigger something big in the age of the specificity or contingency of meaning. Most analysts would reject taking them as isolated cases but part of the spiral of the intolerance that is at the heart of identity, citizenship and violence across the country.

Gov Abubakar Yari of Zamfara State

Anybody who has worked in a far northern state and found him or herself in the grip of concern for safety of corper sons, daughters, sisters and so on from parents, guardians outside the region, the case in Zamfara must be a hair-raising development. Gusau must have sent a signal again that we are all wrong to assume that every corper anywhere at all in the country is protected from arbitrariness by their signature uniform. The uniform seems not enough guarantee of the security of corpers anymore, a situation that it might help if the position is adopted that nobody, other than the directorate, should discipline corpers anywhere in the country. Some people would also not consider it too much to put corpers on the same scale as soldiers and policemen: the message has sunk in this country that there is a price to pay if you wilfully maltreat any of these men and women anywhere in the country. That message was sent in some lamentable way but the message has sunk nonetheless. Many may even argue that corpers should rank higher than soldiers in this scaling. Soldiers signed to die for the country, corpers are sent on a national assignment in recognition of their existing skills and potentials for the country. A corper could die anywhere, anytime, depending on his or her destiny but let it not come from any individual or group error of judgment.

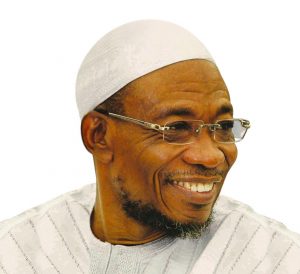

Gov Rauf Aregbesola of Osun State

The host/stranger violence in Ile-Ife that warranted deployment of soldiers and declaration of curfew by the Osun State Government must also be considered as a symptom of the crisis of identity, citizenship and co-existence. All the accounts of what triggered the violence just do not add up. And most analysts would, again, take it as expression of the tension and tendency to unwarranted aggression that have built up everywhere in the country rather than a case of who is right or wrong. Ife is a small place about which the most news is what happens or do not happen at Obafemi Awolowo University, the main modern institution there. The Ife-Modakeke violence of yesteryears is gone from the news for good. Many would, therefore, wonder where this clash is coming from, seeing as this is distinct from herdsmen violence.

There is a risk in news of violence in the provinces. The way they are constructed and the way such construction constitutes its own truth of the violence can be problematic. Pictures from both sites have been circulated, pictures with images that can be deconstructed and transferred to new or different acts of violence. Unfortunately, the social media is a true wonderland in terms of the considerations that would make a newspaper house, a television or a radio station to sanction the use of certain pictures, graphics or spoken words. Without blaming the social media, analysts would say it poses a different kind of challenge to best practices in conflict reporting as understood in traditional journalism.

The elite: former president, Dr Goodluck Jonathan with the late Emir of Gusau, Ibrahim Danbaba

There is a temptation to think that both the Gusau assault, the inter-ethnic clash in Ile-Ife and even the hate-filled representation of each of them are, in the last instance, derivates of the hegemonic contestation within the power elite. It is argued that these acts of violence reflect the deployment of ethno-regional and religious terms by the different fractions within the elite, depending on what is on the table. In other words, a Yoruba-Hausa/Fulani fight is not because these identities are inherently incapable of living together but a function of elite manipulation. Or, that would even not occur at all if it is an elite that holds certain things as absolute as for no citizen or group of citizens anywhere in the country to think of taking the law into his, her or their own hands without paying for it when found out to have done so. From this analysis flows the argument that a calming and reconciliation process is an imperative in Nigerian politics today. This is hinged on the point that the level of suspicion or mistrust in inter-group relations has reached the point where almost nothing is possible again unless and until the folks get a different banner on coexistence from the elite on the national question.

Be that as it may, conflict analysts believe an interim measure is for symbolic or important voices to be heard, categorically condemning whoever is wrong in each of the two flashes, urging the state to ensure that the law takes its course on whoever might have acted irresponsibly at every point in the development of the conflict. Who knows, these flashes could also be the groundwork of people who believe that the north and the south are incompatible or that Nigeria has no business being one country, notwithstanding the great deal of integration that go side by side with the spate of violence.